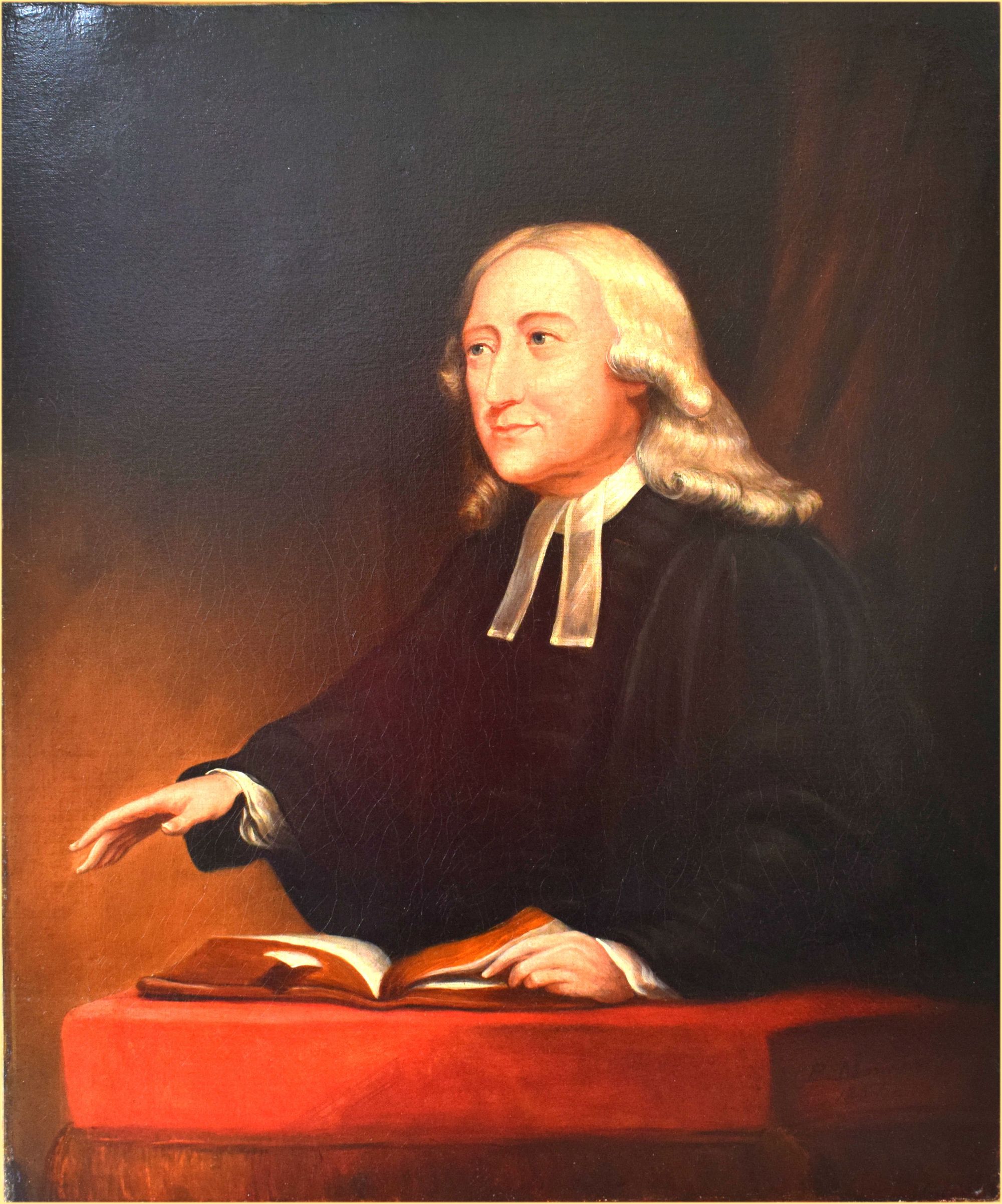

An honest evaluation of the eighteenth-century evangelical revival cannot belittle the central rôle played in it by John Wesley (1703-1791). One thinks, for instance, of his fearless and indefatigable preaching of Christ crucified for sinners throughout the length and breadth of Great Britain after his conversion in 1738. Or of the genius he displayed in preserving the fruit of the revival in small fellowship groups called ‘classes’. Or again, the way he promoted his brother Charles’ matchless hymnody. Yet, for all the good that he did, he was a lightning-conductor for controversy. His propagation of evangelical Arminianism, for example, did much to antagonise other key evangelicals.

Christian perfection

An equally serious error was his commitment to the doctrine of Christian perfection. In the year before his death, he plainly voiced his conviction that God had raised up the Wesleyan Methodists chiefly to propagate this doctrine. Yet, no other doctrine involved Wesley in more controversy than this. It was a key factor in creating a rift between himself and George Whitefield (1714-1770), the leading evangelist in this period of revival. It also alienated him from many of the younger leaders in the revival, like Henry Venn (1724-1797), and even caused some division between himself and his brother Charles.

Convinced that Scripture taught this doctrine, John Wesley was determined to publish it to the world. Yet, unlike his clear presentation of the heart of the gospel, his teaching about perfection is somewhat murky and at times difficult to pin down. He always insisted that he was not advocating ‘sinless perfection’, but he could talk about those who experienced this blessing being ‘saved from all sin, from all unrighteousness’, and having a ‘full deliverance from sin’ — which certainly sounds a lot like sinless perfection! In one of his early sermons entitled Christian Perfection (1739) he plainly declared that it is possible for a Christian to be ‘so far perfect, as not to commit sin’. Such perfection, he claimed, freed the believer from evil thoughts and evil tempers, and so cleansed him from all sin, that unrighteousness no longer remained in his soul.

A change in emphasis?

In other early sermons, Wesley uses similar phrases that sound as if Christian perfection extinguished sin in the believer’s life. However, some of his later writings, especially after 1760, admit that Christian perfection does not totally eradicate indwelling sin. For those who reached this stage in the Christian life, ‘the flesh, the evil nature’, he declared, ‘still remain (though subdued)’. However, Wesley never owned up to what amounted to a significant change in emphasis, and argued that his views had never altered.

It is curious that Wesley himself never claimed to have experienced Christian perfection, or what he sometimes called ‘the second blessing’. But as he preached it, others did apparently receive it, which to his mind was further confirmation of the scriptural truth of the doctrine. In a letter to a friend in 1741, George Whitefield mentions that he had met one of Wesley’s followers who claimed he had not ‘sinned in thought, word, or deed’ for three months. And in the same letter Whitefield mentions a woman who claimed she had been perfect for an entire year, during which time she ‘did not commit any sin’. When he asked her if she had any pride, she brazenly answered, ‘No’! It was from Whitefield that significant opposition to this teaching first came.

Revival in England

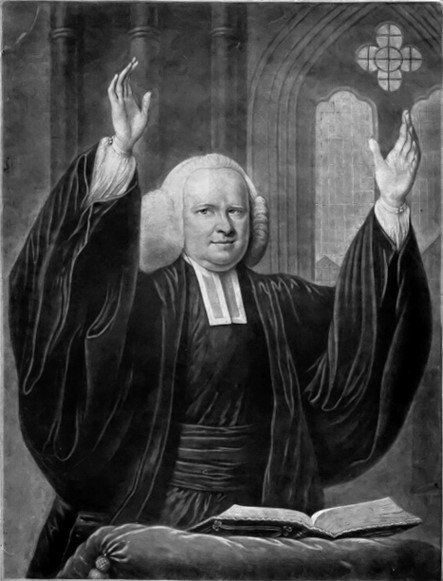

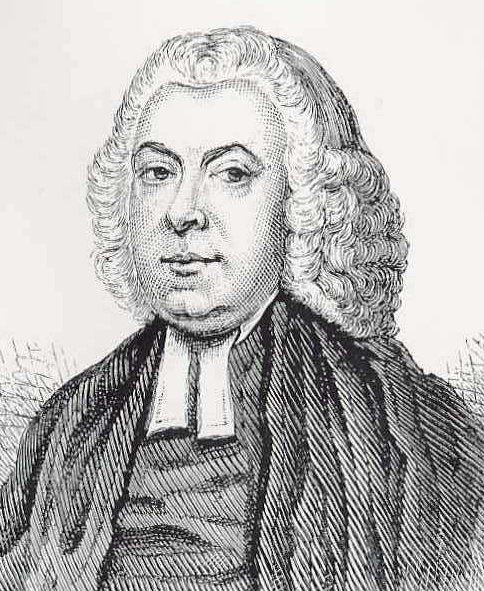

Whitefield had known the Wesley brothers ever since he had gone up to Oxford University in 1732. Soon after his entry to the university he had become a member of their so-called ‘Holy Club’, a group of zealous young men essentially seeking salvation through their own good works. The last to join the club, Whitefield was the first to be converted. It was in the spring of 1735, about seven weeks after Easter, that he discovered the joy of sins forgiven and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. The following year he was ordained a deacon in the Church of England and preached his first sermon.

Within months of this sermon he was in great demand as a preacher, as he spoke powerfully and with authority on justification by faith, the new birth and repentance. In the words of historian Ian Sellers: ‘His preaching style was dynamic and compelling; he spoke with fervour, yet in a style plain, unadorned and often colloquial’. Such preaching, though, was not well received by the majority of the Anglican clergy, and churches began to be barred to him.

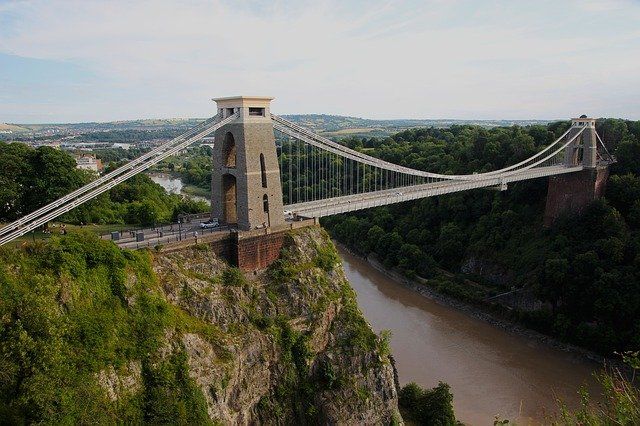

Whitefield, however, was not to be deterred. On 17 February 1739, he took to the open air and preached to a group of coal miners on the outskirts of Bristol, who lived in dire poverty without any church nearby. There were around two hundred at that service. In the words of C.H. Spurgeon, it was ‘a brave day for England when Whitefield began field preaching’. Within weeks, he was preaching thirty or so times a week, to crowds of 10,000 or more!

Long sought by many godly individuals, revival had come to England. And to that revival no man contributed more than Whitefield. Over the thirty-four years between his conversion and his death in 1770 in Newburyport, Massachusetts, it is calculated that he preached around 18,000 sermons. Actually, if one includes all the talks that he gave, he probably spoke about a thousand times a year during his ministry. Moreover, many of his sermons were delivered to congregations of 10,000 or so, and some to gatherings as large as 20,000.

Indwelling sin

With the conversion of both the Wesley brothers in 1738, George Whitefield was joined by two outstanding leaders — John, an intrepid evangelist and superb organiser, and Charles, the supreme poet of love to Christ. Despite his friendship with John, however, Whitefield was not afraid to challenge his erroneous thinking on Christian discipleship.

Between 1740 and 1742 he wrote letters to Wesley and preached a number of sermons which opposed Wesley’s views about Christian perfection. He did so with frankness, but also with evident love. For instance, writing from Savannah, Georgia, on 26 March 1740, he told Wesley that to the best of his knowledge ‘no sin has dominion’ over him, but went on: ‘I feel the strugglings of indwelling sin day by day’. Despite his evident conflict with Wesley, he did not relish the prospect of disagreeing with him. Would not their disagreement, he said, ‘in the end destroy brotherly love, and insensibly take from us that cordial union and sweetness of soul, which I pray God may always subsist between us?’

That September he told Wesley: ‘Sinless perfection…is unattainable in this life. Shew me a man that could ever justly say, “I am perfect”. It is enough if we can say so, when we bow down our heads and give up the ghost. Indwelling sin remains till death, even in the regenerate’. Scriptural support for his position was found by Whitefield in texts like 1 Kings 8:46 (‘there is no man that liveth and sinneth not’) and James 3:2 (‘In many things we all offend’), as well as examples drawn from the lives of King David and the apostles Peter and Paul.

An open letter

Later that year, in November, Whitefield told Wesley; ‘I am yet persuaded you greatly err. You have set a mark you will never arrive at, till you come to glory’. The following month found Whitefield wintering at Bethesda in Georgia. From there he published an open letter against his friend in which he once again dealt plainly with his brother in Christ. On the subject of perfection he confessed that since his conversion he has ‘not doubted a quarter of an hour of having a saving interest in Jesus Christ’. But, he also had to acknowledge ‘with grief and humble shame…I have fallen into sin often’. Such a confession, though, was not unique to him; it was the ‘universal experience and acknowledgment…among the godly in every age’.

Wesley lampooned Whitefield’s view as being ‘for sin’, while he was ‘for holiness’. Whitefield’s perspective, however, rested squarely on the testimony of Scripture, on an adequate theological analysis of indwelling sin, and on the testimony of God’s people down the history of the church.

Nevertheless, Wesley’s teaching had enormous influence in the century after his death in 1791. It formed the heart and substance of the transatlantic Holiness Movement of the nineteenth century. Wesley’s godly lieutenant, John Fletcher (1729-1785), described Christian perfection as ‘the baptism of the Holy Spirit’, and thus prepared the soil for the emergence of Pentecostalism in this century.

A different history?

What would the history of the Evangelicalism have been like if Wesley had listened to Whitefield? We have no way of knowing, of course, for God’s sovereignty deemed otherwise. But it strikes this writer that his brother Charles came to a much more clear and balanced perspective on this matter than did John. The younger Wesley once told the great Yorkshire evangelist William Grimshaw (1708-1763); ‘My perfection is to see my own imperfection; my comfort, to feel that I have the world, flesh, and devil to overthrow through the Spirit and merits of my dear Saviour; and my desire and hope is to love God with all my heart, mind, soul, and strength, to the last gasp of my life. This is my perfection. I know no other, expecting to lay down my life and my sword together’.