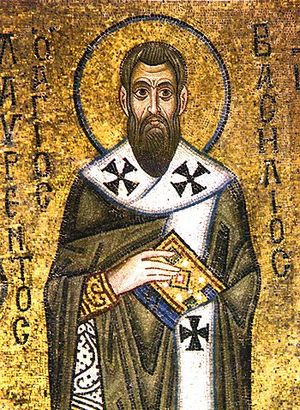

While the first book devoted to the subject of baptism was written by the North African theologian, Tertullian, at the end of the second century AD, it was not until the middle of the ninth century that a book on the Lord’s Supper appeared. Similarly, while there were a number of books on the person and work of Christ in the early centuries, it was not until Basil of Caesarea (c.329-379) wrote his On the Holy Spirit in 375 that there was a book specifically devoted to the person of the Spirit of God.

We know more about Basil than any other Christian of the ancient church, apart from Augustine of Hippo. Central to our knowledge of his life is a marvellous collection of some three hundred and fifty letters.

Basil was born around 329 in the Roman province of Cappadocia (now central Turkey). His family was fairly well-to-do, with his father, also called Basil, being a teacher of rhetoric (i.e. the art of public speaking), and his mother Emmelia coming from landed aristocracy. The family’s Christianity can be traced back to Basil’s paternal grandmother, Macrina. Of Basil’s eight siblings we know the names of four: Macrina, Naucratius, Peter, later the Bishop of Sebaste in Armenia, and Gregory of Nyssa, one of the leading theologians of the fourth century.

Conversion

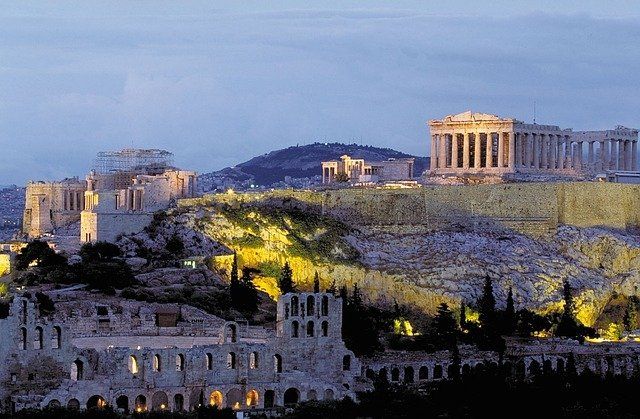

Basil went to school at Caesarea, as well as at Constantinople, and then, in 350 or so, he went to study in Athens, where he became a close friend of Gregory of Nazianzus, another of the great Greek theologians of this era. In 356 Basil returned to Caesarea, hoping to open a school of rhetoric. His older sister Macrina, however, challenged him to give his life unreservedly to Christ. So it was in that same year that Basil was converted. He says, ‘I wasted nearly all of my youth in the vain labor that occupied me in the acquisition of the teachings of that wisdom which God has made foolish. Then at last, as if roused from a deep sleep, I looked at the wonderful light of the truth of the gospel, and I perceived the worthlessness of the wisdom of the rulers of this age, who are doomed to destruction. After I had mourned deeply for my miserable life I prayed that guidance be given to me for my introduction to the precepts of piety’ (Letter 223).

Now, Basil’s conversion to Christ was also a conversion to a monastic lifestyle. Basil never had the impression that the such a lifestyle was for every believer. Yet, he did believe that in fourth-century Greco-Roman society, where Christianity was fast becoming the only tolerated religion and where many were now flocking into the church for base motives, monasticism was a needed force for church renewal. In time, during the 360s, Basil became a leading figure in the establishment of monastic communities, which he sought to model after the experience of the Jerusalem church, as it is depicted in the early chapters of Acts.

After founding a number of monasteries, he was ordained in the mid-360s. He became Bishop of Caesarea in 370. As bishop, Basil fought simony and established hospitals — the first hospitals in the ancient world, apart from those attached to the Roman army. He aided the victims of drought and famine, insisted on ministers living holy lives, was fearless in denouncing evil wherever he detected it, and excommunicated those involved in the prostitution trade in Cappadocia.

Fighting against the Spirit

Basil was not only a Christian activist. He was also a clear-headed theologian. Athanasius, the great defender of Trinitarian Christianity, had died in 373, and Basil inherited his mantle. Arianism, which denied the deity of both the Son and the Holy Spirit, and which Athanasius had combated, was still widespread in the eastern Mediterranean. There is little doubt that Basil played a key role in the victory of orthodox Trinitarianism over Arianism in this region of the Roman Empire.

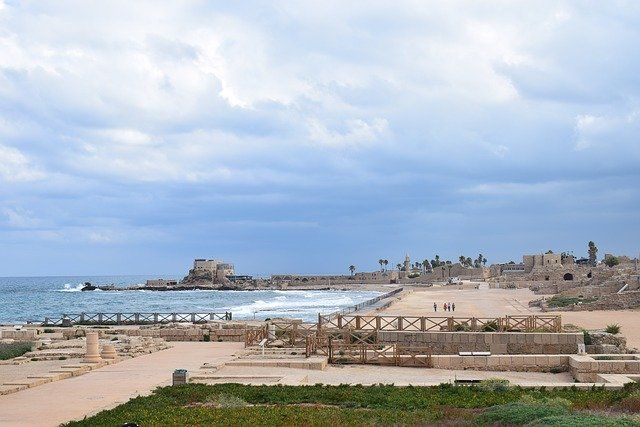

In the early 370s, though, Basil found himself locked in combat with professing Christians who, though they confessed the full deity of Christ, denied that the Spirit was fully God. Leading this movement of ‘fighters against the Spirit’ (Pneu-matomachi), as they came to be called, was one of his former friends. Indeed, it was the man who had been his mentor when he first became a Christian in 356, Eustathius of Sebaste (c.300-377). Eustathius’ interest in the Spirit seems to have been focused on the Spirit’s work, not on his person. For him, the Holy Spirit was primarily a divine gift within the Spirit-filled person, one who produced holiness. When, on one occasion at a synod in 364, he was pressed to say what he thought of the Spirit’s nature, he replied, ‘I neither choose to name the Holy Spirit God, nor dare to call him a creature!’

For a number of years Basil sought to win Eustathius over to the orthodox position. Finally, in the summer of 373, he met with him for an important two-day colloquy. After much discussion and prayer, Eustathius agreed to sign a statement of faith in which it was stated: ‘[we] must anathematize all who call the Holy Spirit a creature, and … all who do not confess that he is holy by nature, as the Father is holy by nature and the Son is holy by nature, and refuse him his place in the blessed divine nature …We have been taught that the Spirit of truth proceeds from the Father, and we confess him to be of God without creation’ (Basil, Letter 125).

A second meeting was arranged for the autumn of 373, at which Eustathius would sign this declaration in the presence of a number of Christian leaders. But, on the way home from his meeting with Basil, Eustathius was convinced by some of his friends that Basil was theologically in error. For the next two years Eustathius criss-crossed what is now modern Turkey, denouncing Basil and claiming that he was the heretic, one who believed that there were absolutely no distinctions between the persons of the Godhead. Basil was so stunned by what had transpired that he kept his peace for nearly two years. Finally, he simply felt that he had to speak. These words are found in one of the most important books of the entire patristic period, On the Holy Spirit.

The Spirit is God

After showing why Christians believe in the deity of Christ (chapters 1-8), Basil devotes the heart of his treatise to demonstrating from Scripture why the Spirit is to be recognized as God. The Spirit gives insight into divine mysteries, since he plumbs the depths of God (1 Corinthians 2:10), something only one who is fully divine could do. He enables men and women to confess the true identity of Christ and to worship him (1 Corinthians 12:3). He gives spiritual gifts ‘as he wills’ (1 Corinthians 12:11), an indication of his sovereign Lordship over the church. He is omnipresent (Psalm 139:7), an attribute possessed only by God. He is called ‘God’ by Peter (Acts 5:3-4).

In the words of chapter 9, which introduces Basil’s study of the Spirit’s person and work in Scripture, Basil states by way of anticipation what he will seek to show.

‘He perfects all other beings, but he himself lacks nothing … He does not grow or increase, but is immediate fullness, firmly established in himself, and omnipresent … From him comes foreknowledge of the future, understanding of mysteries, comprehension of hidden realities, distribution of spiritual gifts, the heavenly citizenship … everlasting joy, abiding in God … Such then, to mention only a few of many, are the conceptions about the Spirit, which we have been taught by the oracles of the Spirit themselves [i.e. the Scriptures], to hold about his greatness, his dignity and his activities.’

Basil died in 379, worn out by hard work and illness. Two years later, the Council of Constantinople incorporated Basil’s defence of the Spirit’s essential deity into the credal statement known as the Nicene Creed. The article on the Spirit, deeply influenced by Basil’s On the Holy Spirit, was probably written by Basil’s younger brother, Gregory of Nyssa. It is a landmark statement in the history of the church and runs thus. ‘We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who is worshipped and glorified together with the Father and the Son, who spoke through the prophets.’