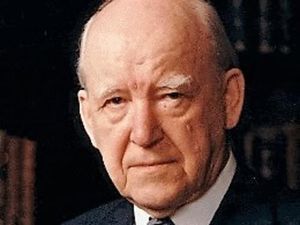

This is the second of two articles on Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones and the nature of genuine evangelicalism. The first, which appeared in last month’s Evangelical Times, traced his life and ministry up to the fateful meeting organised by the Evangelical Alliance in 1966. It was at this meeting that the chairman, John Stott, took the speaker, Martyn Lloyd- Jones, to task for advocating that evangelicals should withdraw from apostate denominations. The divisions within British evangelicalism, always present beneath the surface, were thus consolidated and made clear for all to see.

Wrong divisions

Four years later, in 1970, Lloyd-Jones was asked to speak at the annual conference of the British Evangelical Council (BEC), which had been founded in 1952 as an evangelical response to the false ecumenism of the World Council of Churches (founded in 1948). The paper he delivered on that occasion was titled ‘Wrong divisions and true unity’, and has recently been published in Unity in Truth.

Taking the apostle Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 15:1-4 as his text, Lloyd-Jones introduced his talk by pointing out that the age in which he and his hearers were living was, in his opinion, ‘characterised above everything else…by confusion’. This confusion was evident not only in the world but, sadly, also in the ranks of evangelicals.

Confusion in the evangelical camp was cause for deep concern, declared the Welsh preacher, since ‘the greatest need in the world tonight is for a united evangelical message. It is the only hope for mankind. It is the only hope for the world and, in general, it is the only hope for the church’. There is little doubt that, basically, Lloyd-Jones viewed genuine evangelicalism as biblical Christianity.

He then proceeded to outline some wrong reasons for professing evangelicals to divide from one another. He mentions things such as the differing personalities of church leaders (rebuked by Paul in 1 Corinthians chapters 1, 3 and 4), and what he calls ‘false spirituality’, the ever-present tendency to divide about spiritual gifts, which Paul censures in 1 Corinthians 12-14. There were, however, various things that evangelicals ‘must regard as essential’ and over which, Lloyd-Jones stressed, they ‘must be prepared to separate’ if they are denied. Lloyd-Jones identified four key essentials in this regard.

Essentials

First, evangelicals must continue to affirm that the Scriptures are divine revelation and God-breathed, and, as such, authoritative. Furthermore, their authority extends not only to matters relating to salvation and ethics but also, Lloyd-Jones emphasised, to what they have to say about creation and history.

Here, Lloyd-Jones was specifically responding to some evangelicals who, since the 1960s, have been quite prepared to admit Scripture’s authority in matters of religious truth, but who are unwilling to acknowledge that authority when it comes to matters of science or history. But, as Lloyd-Jones rightly pointed out, such an emphasis is ‘a departure from evangelicalism — a departure that will deprive us of all our authority and begin among us a slide into liberalism and even to Roman Catholicism’.

A second essential is ‘the doctrine of the Fall and the need of salvation’. Third, there is the plan of redemption that has as its heart the death of Christ for sinners. Finally, evangelicals must hold fast to Paul’s teaching about Christ’s substitutionary death for sinners, his ‘literal, physical resurrection’, and the blessed hope of his second coming.

As Lloyd-Jones reads 1 Corinthians 15, these are the key beliefs that he sees the apostle Paul making central. Evangelicals must therefore stand on them ‘unflinchingly, without the slightest suspicion of accommodation or modification’. In other areas, though, evangelicals must bear with one another. If they do not, and if they separate over what is not essential, they can only be regarded as guilty of schism.

What is an evangelical?

Possibly Lloyd-Jones’ most important study of these issues came in three addresses that he gave at the 1971 IFES Conference, held that year at Schloss Mitersill, Austria. These addresses have recently been published as a pamphlet, What is an evangelical? by the Banner of Truth.

In the first talk Lloyd-Jones begins by emphasising the pressing need for a contemporary definition of the word ‘evangelical’. Contrary to those who maintained that ‘we all know what an evangelical is; it’s a familiar term’, Lloyd-Jones stresses that since the 1960s the whole meaning of the term has been called into question. How to define this term is, Lloyd-Jones was convinced, ‘the great question today’. It will remain a question that evangelical believers will have to face increasingly in the years to come. ‘For us to assume’, he argues, ‘that because we have once said that we are evangelical, therefore we must still be evangelical now and shall always be, is not only to misread the teaching of the New Testament, but to fail completely to grasp and to understand the great lessons which are taught us so clearly by history’. Lloyd-Jones is clearly thinking of denominations and Christian bodies which began their existences as solidly evangelical but which, in the course of time, underwent subtle changes, not only in emphasis but also with regard to ‘vital and essential matters’.

It is noteworthy that Lloyd-Jones makes it clear that he is not interested in division over secondary, let alone third-rate or fourth-rate issues. A ‘fissile tendency’, Lloyd-Jones states, has dogged the history of evangelicalism. Evangelicals must therefore guard against being ‘so rigid, so over-strict, and so narrow that we become guilty of schism’.

Reason subservient to Scripture

In his second lecture Lloyd-Jones focused on the ethos of evangelicalism, what he calls ‘certain general characteristics of the evangelical person’. Among them are such things as submission to God’s Word; a willingness to examine all traditions in the light of that Word; a commitment to simplicity in matters such as church government and worship; a concern to uphold the vital importance of the new birth and a subsequent life of piety; and an emphasis on evangelism.

One of the characteristics that Lloyd-Jones lists here would be questioned by some, namely, his insistence that the evangelical ‘distrusts reason and particularly reason in the form of philosophy’, and is wary of trusting in scholarship. Strong words! What Lloyd-Jones is commending, however, is not anti-intellectualism or obscurantism, attitudes he is quite prepared to condemn. Rather, he is stressing the need to keep reason and scholarship in their proper place in the Christian life, always subservient to Scripture.

A. T. B. McGowan notes with regard to this section of Lloyd-Jones’ lectures: ‘This is a most helpful section and needs to be heard loudly and clearly in theological colleges today, where Enlightenment principles and values (rather than biblical ones) are often in control’.

Not just doctrine

Lloyd-Jones devoted this second lecture to a discussion of the ethos of evangelicalism, since he was convinced that to define evangelicalism solely in terms of doctrine is a major mistake. Such a pathway would invariably lead to dead orthodoxy. Evangelicals, he insists, are concerned about life as well as doctrine. Thus, he says, ‘you will always find in evangelical circles that there is great emphasis on the study of the Bible, personal and corporate, that great attention is paid to expositions of the Scripture and to prayer’.

Foundations

The third and closing lecture differentiates between ‘essential or foundational’ truths and ‘others concerning which there can be a legitimate difference of opinion’. Among such non-essential issues Lloyd-Jones places things like differences over the nature of election and predestination, the age and mode of baptism, questions about church government, the issue of the millennium, and the whole debate about the baptism of the Spirit and the spiritual gifts.

However, refusal to make such issues the ground of separation should not be taken to imply that doctrine is not important. As Lloyd-Jones vehemently states: ‘we have to assert and defend the position that doctrine is really vital and essential’.

There is something of a contradiction here. If doctrine is ‘essential’, how can some specific doctrines such as election be ‘non-essential’? The solution to this problem lies in the question ‘essential for what’? Writing of ‘non-essential’ doctrines Lloyd-Jones says, ‘We call them non-essential because they are not essential to salvation’ (Knowing the Times, Banner of Truth, 1989, p. 351). He goes on: ‘we must always remember that we are not saved by our understanding… There is also a difference between a defective understanding and a positive denial of truth…’

Thus among saved people there may be doctrinal differences arising from a defective understanding on the part of some. Those with a mature understanding must not separate from or dismiss truly regenerate people who cannot digest strong meat. But this does not mean that we must compromise the clarity of the gospel to accommodate unbiblical or immature ideas!

What is essential?

As to those doctrines which Lloyd-Jones considers absolutely essential for the name ‘evangelical’ to have meaning, he lists five. First, Scripture is confessed by evangelicals to be the sole authority for the believer’s thought and life. This entails a clear indication that all of Scripture is divine revelation, in matters relating to history and science as well as to salvation — all of it must be recognised as given by the Spirit of God.

Second, evangelicals are clear in their affirmation of the biblical teaching about creation and the historical nature of Genesis chapters 1 and 2. Third, evangelicalism asserts the historicity of the Fall, which necessarily involves the recognition of a personal devil and the fact of ‘total depravity’.

The fourth area of doctrine has to do with the way of salvation. Here, Lloyd-Jones underscores the need for evangelicals to emphasise first that the cross-work of Christ is substitutionary, penal and particular. The second critical area with regard to salvation is that this saving work is a work of grace, appropriated solely by faith. Justification, in other words, is by faith alone.

Finally, Lloyd-Jones maintains that evangelicalism necessarily involves a certain perspective on the church. For instance, it rejects any idea of the sacraments being efficacious in and of themselves and will not allow the division of God’s people into clergy and laity.

Conclusion

To sum up, a number of items occur more than once in these definitions of evangelicalism. Genuine evangelicalism (1) holds the Scriptures to be God-breathed being, in their entirety, revealed truth and the sole authority for the believer. It affirms (2) that salvation is found solely in Christ and his death for sinners. Then (3) evangelicalism asserts that this salvation is by grace and is appropriated by faith alone. It emphasises (4) that all men and women are in a state of total depravity, desperately in need of the new birth. Finally (5) it confesses faith in the reality of Christ’s miraculous life, especially his virgin birth, physical resurrection and second coming.

The first three of these five items recall the key biblical truths rediscovered at the time of the Reformation, those summed up by the slogans, sola Scriptura, solus Christus, sola fide. In other words, central to Lloyd-Jones’ definition of what it means to be an evangelical are the main emphases of Reformation doctrine. The emphasis on total depravity can also be found in the writings of the Reformers. His stress, though, on the new birth, is derived from the Puritans and the revivals of the eighteenth century. The final item, emphasising the reality of the supernatural elements in the life of Christ, is clearly a response to the still-present threat of liberal theology.

Yet, as we have seen from Lloyd-Jones’ 1971 addresses to the IFES, he would not be satisfied if our discussion of evangelicalism’s nature were restricted to the doctrines it affirms. To be sure, genuine evangelicalism is rooted in right doctrine. But it also longs to experience the power of these doctrines in the soul.

As Lloyd-Jones once remarked regarding Jonathan Edwards, that quintessentially evangelical theologian: ‘Nothing is more striking than the balance of this man. You must have the theology; but it must be theology on fire. There must be warmth and heat as well as light. In Edwards we find the ideal combination — the great doctrines with the fire of the Spirit upon them’.