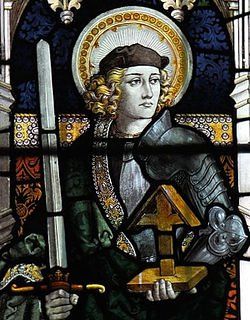

Alban is the most famous of Britain’s earliest Christian martyrs, and Bede gives us some details about his conversion and death.

When the Roman persecution began, Alban was still a pagan but a kind-hearted one. He sheltered a Christian who was fleeing from his persecutors.

As he observed the godliness of this man, Alban, ‘was suddenly touched by the grace of God’ and began to receive instruction from his guest concerning the way of salvation. Before long, ‘Alban renounced the darkness of idolatry, and sincerely accepted Christ’.

Escape route

Eventually the ruler of the area got wind of the Christian’s whereabouts and sent his soldiers to Alban’s house. When they arrived, Alban refused to betray his friend and gave himself up instead.

He was bound and taken before the judge. At his trial Alban confessed his new-found faith. He was then offered the opportunity to renounce Christ and prove that he meant it by offering a sacrifice to the idols.

It was normal Roman practice to offer a get-out for people on trial for their religion. In later times, when greater laxness had crept into the Church, professing Christians who were not sincere would be glad to take the escape route.

Obviously, true and faithful believers would resist pressure to acknowledge the pagan gods, and Alban steadfastly refused. He was therefore flogged but, Bede says, ‘for Christ’s sake, he bore the most horrible torments patiently and even gladly’. The judge therefore ordered his immediate execution.

History

The earliest really conclusive information that we have about the presence of Christianity in Britain dates from the year 314, when five British church leaders were present at the Council of Arles in southern France.

To understand the significance of this Council we need to know something about the history that led up to it.

In the years just prior to 314, events of far-reaching significance had taken place in the British Isles. During Diocletian’s reign, the Roman Empire had been subdivided into four parts, two governed by a senior emperor (an augustus) and the other two by an assistant emperor (a caesar).

The second augustus was called Maximian. The two caesars were Galerius and Constantius. The latter was the mild politician to whom we made reference last month. He was allocated the north-western provinces, including Britain.

In the year 305, Diocletian and Maximian abdicated. Constantius and Galerius were elevated to the rank of augustus, and two new caesars were appointed (Maximin in the east and Severus, under Constantius, in the west).

A year later, Constantius died in York. He was succeeded as augustus by his 32-year-old son Constantine, who happened to have joined his father in Britain a few months earlier. This succession was unconstitutional.

Severus ought to have succeeded Constantius as augustus, and a new caesar should have been appointed over the north-western provinces. Despite the opposition of Galerius, Constantine consolidated his position, largely by force of arms. Eventually (in 324) he became sole ruler over the entire Empire, having ruthlessly disposed of his rivals.

Tactic

Constantine’s most famous victory took place in Italy in 312, when he defeated one of the other emperors at the Milvian Bridge over the River Tiber, and so extended his influence eastwards into central Europe.

Before the battle, Constantine sensed the need for divine aid for his troops. He found the polytheism of Roman paganism repulsive, and so turned for help to the God of the Christians.

Constantine may have been influenced in this direction by the presence amongst his troops of British Christians. We know from the writings of Zosimus, a fifth century pagan historian, that there were British soldiers amongst the forces that Constantine took to Italy. It is possible that some of them had become Christians.

Eusebius informs us that Constantine’s decision to invoke the help of ‘the supreme God’ was clinched by a vision he had of a cross in the noonday sky. The vision carried the inscription, ‘Conquer by this’.

Another fifth century historian, a Christian called Sozomen, tells us that after seeing this vision Constantine sought instruction in Christian doctrine from some of the pastors of the churches.

He also informs us that these experiences occurred while Constantine was still in the north-west of the Empire before setting out to fight his rival. Thus these events could have taken place in the British Isles.

I do not think this means that Constantine was truly converted. He certainly gave his endorsement to Christianity, but did so largely as a military and political tactic.

Council of Arles

It was just two years after Constantine’s victory at the Tiber that the Council of Arles took place. In the intervening year an edict passed at Milan had proclaimed religious toleration throughout the Empire. State persecutions against the Christians, like the one in which Alban had died, came to an end.

This presented the churches with a problem. During the last official persecution, while Diocletian was the senior emperor, there had been some pastors who did succumb to the pressure and proved unfaithful.

The emperor had commanded all Christian pastors to surrender the Scriptures. Failure to do so would result in imprisonment or death. Sadly, some pastors had complied.

Once the persecution was over the churches had to face the issue of whether or not such pastors could be readmitted to the ministry. In North Africa differences of opinion led to a full-blown division, with two competing church bodies.

The rigorous Donatists opposed readmission, while the more lenient Caecilianists advocated forgiveness. The two parties were named after their leaders: Donatus and Caecilian became rival pastors at Carthage, an important city on the north coast of Africa in modern-day Tunisia.

At a meeting in Rome in October 313, nineteen church leaders from Italy and France tried to resolve the dispute. They decided in Caecilianists favour and the Donatists appealed to Constantine requesting a new hearing. The outcome was the Council of Arles, which again backed the Caecilianists.

The five British representatives at the Council included three leading pastors, Eborius from York, Restitutus from London, and Adelphius from ‘Civitate Coloniae’. (We cannot be sure where this place was; suggestions include Lincoln, Caerleon and Colchester.)

The presence of these men at Arles testifies to the respect in which the English (and possibly Welsh) churches were held at the beginning of the fourth century by the international Christian community.

The Druids

We can be sure, then, that the church was firmly established in the British Isles well before this time. But what was the religious environment into which the seed of the gospel had to be planted?

Gildas describes pre-Christian Britain as a place of diabolical idolatry. He indicates that the ancient Britons worshipped more idols than the Egyptians in their heyday! He says that the people paid divine honour to mountains and rivers, and quotes a proverb – ‘the Britons are neither brave in war nor faithful in time of peace’.

One interesting fact about British people of that time, according to Tertullian, is that it was customary amongst males to wear tattoo-marks!

It is sometimes said that the religion of Britain in the early centuries of the Christian era was Druidism. Actually, it seems that the Druids were just the teachers of their day.

They presided at religious ceremonies, but it is not clear that they had their own religion. They seem to have taken over whatever religion was traditional in any given place.

In The Gallic Wars Julius Caesar gives us a few snippets of information about the Druids. His observations relate to Gaul, but he does say that Druidism originated in Britain and crossed the Channel from here.

He also notes that those who wanted to improve their knowledge of Druidism generally went to Britain to study it.

Ancient gods

Caesar thought that the Druids’ most important teaching was the belief that ‘souls do not become extinct, but pass after death from one body to another’. Apparently, the Britons did not believe in resurrection and a final judgement, but in continuous reincarnation for the soul in a succession of human bodies.

Caesar also indicates that the Druids were polytheistic. The names of 374 ancient British gods have been identified, though the majority were patron deities of particular localities. The main pantheon of early British deities numbered just 33.

Caesar characterises the Gauls as ‘devoted to superstitious rites’. He mentions human sacrifice as an example. It is uncertain whether this was a universal Druidic practice, and it is impossible to say whether human sacrifice was practised in Britain.

To such a people, says Gildas, came the beams of the light of Christ. His assessment is that the reception of the gospel in Britain was ‘lukewarm’. Nevertheless, the gospel ‘took root among some of them in a greater or lesser degree’.