In a year of royal birthdays it is appropriate to recall another, celebrated more than four hundred and fifty years ago. On that day, bells peeled out across London, guns from the Tower of London thundered over two thousand salutes, and bonfires lit up the night sky. At last King Henry VIII had a son and heir!

Born on 12 October 1537, Prince Edward was the son of Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour. But, despite the celebrations, he had an unhappy beginning to life. When only twelve days old his mother died unexpectedly of complications arising from the birth.

The king was frenetic over his infant son’s health. Smothered in shawls to prevent any draughts reaching him, Edward spent his early months in a purpose-built nursery at Hampton Court. Twice daily his rooms were scrubbed and swept, and no visitors were allowed near the babe.

Family life

Although Edward was a cheerful youngster, one thing was missing. The motherless prince knew little true affection. All was soon to change, however, with his father’s final marriage to Catherine Parr in 1543. At last the six-year-old experienced some family life, as Catherine insisted that Edward and his half-sister Elizabeth spend more time with their parents.

Edward’s response to his stepmother’s affection was immediate and strong. More than this, Catherine arranged for boys of Edward’s own age, sons of the nobility, to join him in his schoolroom.

As the prince’s education began in earnest, we see God’s overruling hand, both for Edward and the future of the Christian church in England. Henry VIII had vacillated between Roman Catholicism and the Reformation for the best part of his reign, persecuting the adherents of first one and then the other. A pragmatist to the last, he decided that the Tudor posterity would best be served by a Reformed upbringing for his son.

Achievement

Richard Cox and John Cheke were appointed to be the boy’s tutors. Both were well-known friends of the Reformation, the movement that was rapidly restoring the Bible to the centre of the Christian religion after centuries of neglect.

It is evident that Edward was an exceptionally able child. By the time he was seven he was reading Latin texts fluently, and soon French and Greek were added to his timetable.

A weighty tome of his childhood writings has survived, containing fifty or more lengthy Latin essays and as many in Greek. A school report – had there been such a thing then – would have complimented the prince on all-round achievement. However, we are told that the royal Tudor bottom was smacked when young Edward grew tired of memorising the book of Proverbs in Latin!

At nine years of age the prince undertook his first royal responsibilities, welcoming the Admiral of France as he arrived on a state visit. Three brief months later, the weight of kingship fell on the child’s shoulders as he learnt of his father’s death in January 1547.

Boy-king

Then came the elaborate ceremony of coronation. The boy-king, clad in a gown of woven gold with a cape of white velvet decorated with rubies and diamonds, was escorted on a horse draped in crimson, first to the Tower of London and then to Westminster Abbey.

A long and tedious ceremony, Edward was allowed short rests during that lengthy day. The crown was heavy for a nine-year-old head and (recording his memories in his personal journal) Edward commented dolefully that he was obliged to wear it throughout a banquet that followed the ceremonies! He crept into his bed that night a weary child.

Effective rule of the country during Edward’s minority was entrusted to a Council of Regency comprising sixteen men. Edward Seymour, the prince’s uncle, was in overall charge with his other uncle, Thomas Seymour, also in a prominent position.

When Thomas Seymour married the boy’s stepmother, Catherine Parr, Edward was not above playing off one uncle against the other, particularly if he was in need of extra pocket money!

Evangelical convictions

By surrounding his son with men of evangelical principles, Henry VIII did more than he intended. Before long it was evident from Edward’s own writings that his personal sympathies lay with the Bible-based teaching of the Reformation. Later these same truths became his own deeply held beliefs.

One person whose influence seems to have been crucial to the boy’s understanding of Christian truth was his French master, Jean Belmain. Edward’s French essays reveal the intensity of the boy’s evangelical convictions.

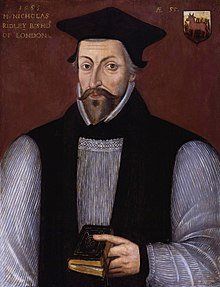

With Edward’s support, the reformation of the English church went ahead at an astonishing pace. Edward loved to hear sermons and made detailed notes of addresses from preachers such as Nicholas Ridley. Sadly, his notebook has not survived. Archbishop Cranmer’s revised Book of Common Prayer came into use in 1552.

All this was not fast enough for the young king. When John Hooper, about to be consecrated as Bishop of Gloucester, learned that the service required him to wear certain vestments and take an oath in the name of the saints, he objected strongly. Such ideas, he maintained, were unbiblical. Who should come to his rescue but the thirteen-year-old king?

‘Are these offices ordained in the name of saints or of God?’ he enquired imperiously, and with one stroke of his pen slashed through the offending words in the prayer book service. Edward was clearly a Tudor monarch in the making.

Threat of war

A yet more notable scene took place shortly after this – a high profile scene of predictable tension between the thirteen-year-old king and his half-sister Mary, now in her thirties. Mary, a devout Roman Catholic, wished to celebrate mass in private. Mary wept and begged for her young brother’s permission. Edward also wept, but was adamant. Mary departed insisting that she would emigrate rather than comply.

However, Mary’s closeness to her cousin, Charles V, now Holy Roman Emperor, confounded the situation. To offend Mary could have serious political consequences for England. The Emperor’s anger was unleashed against England, and he instructed his ambassador to threaten war.

Edward’s councillors arrived. On their knees these anxious men urged the gravity of the situation and begged Edward to compromise. Only when the boy threatened to burst into tears did they retire defeated. War did not follow: just a dramatic, but failed, rescue attempt to remove Mary from the country.

Succession

In February 1553, Edward, still only fifteen years of age, but now taking an active part in government, caught a heavy cold. It seemed harmless enough, but he was unable to shake it off. As spring turned to summer it became clear that he was seriously ill. Those about him noted with alarm the harsh dry cough and burning fever that never seemed to leave him. Unable to rest or eat, with inflamed lungs, Edward was clearly dying.

One thing troubled him. He knew that under his father’s will the crown would pass to his half-sister, Mary. He feared that the progress of Bible-based Christianity in England, for which he, his bishops and his councillors had worked so assiduously, would be halted.

The only answer was to change the succession. Some have said that the sick boy was manipulated, but there is no reason to doubt that Edward knew his own mind. Aided by the Duke of Northumberland, he planned to leave his throne to his sixteen-year-old cousin, Lady Jane Grey, an earnest Christian girl.

When lawyers were summoned to effect the change, they hesitated. Not until the sick boy had demanded that they comply was the will officially altered in favour of Lady Jane.

Dying prayer

Now Edward was at peace. Turning to the wall he began to pray:

‘Lord God, deliver me out of this miserable and wretched life, and take me among thy chosen: howbeit, not my will but thy will be done. Lord, I commit my spirit to thee. O Lord! Thou knowest how happy it were for me to be with thee: yet for thy chosen’s sake, send me life and health, that I may truly serve thee.

‘O Lord my God, bless thy people. O Lord God save thy chosen people of England! O my God defend this realm … and maintain thy true religion, that I and my people may praise thy holy name, for thy Son Jesus Christ’s sake’.

Then Edward became conscious that he was not alone: his doctor was standing nearby.

‘I thought you were farther away’, he said. ‘We heard you talking to yourself’, said the doctor. ‘I was praying,’ replied Edward simply.

Three hours later Edward spoke his last words: ‘I am faint. Lord have mercy upon me and take my spirit’. On 6 July 1553, Edward, the zealous and able young king, died. Despite his attempts to change the will, Mary raised an army, defeated troops loyal to Lady Jane, and ascended to the throne.