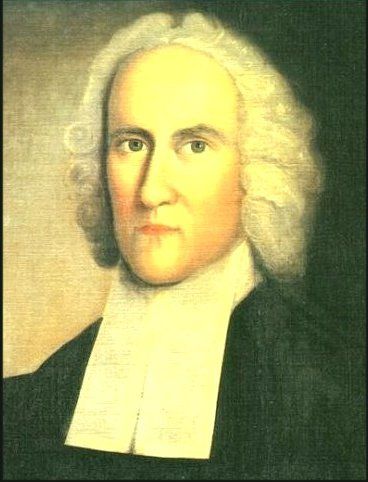

In recent articles we have looked at the spirituality of Jonathan Edwards, considered by many to be a classical mentor in this area of the Christian life. But his wife, Sarah Pierrepont Edwards (1710-1758), appears to have had as rich a walk with Christ as her famous husband.

Unfortunately, Sarah was not a writer and left neither an extensive journal nor substantial correspondence to record her spiritual life. But in the course of this article we will look at one remarkable manuscript from her hand which provides an insight into the workings of her heart. For the early part of her life, however, we must rely on the words of others, especially those of her husband and his first biographer, Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803).

Spiritual maturity

Jonathan’s first recorded words about Sarah were penned in 1723 in the front page of a Greek grammar. ‘They say there is a young lady in [New Haven] who is beloved of that Great Being, who made and rules the world, and that there are certain seasons in which this Great Being … comes to her and fills her mind with exceeding sweet delight, and that she hardly cares for any thing, except to meditate on him – that she expects after a while to be received up where he is, to be raised up out of the world and caught up into heaven; being assured that he loves her too well to let her remain at a distance from him always.

‘There she is to dwell with him, and to be ravished with his love and delight forever. Therefore, if you present all the world before her, with the richest of its treasures, she disregards it and cares not for it, and is unmindful of any pain or affliction’.

At the time this was written, Jonathan was twenty and Sarah but thirteen! Though too young to court, Jonathan was clearly taken with Sarah’s piety, spiritual maturity, and the fact that her outward deportment matched her inner spirituality.

Spiritual heritage

Like her future husband, Sarah had been born into a family with a rich spiritual heritage. Her father, James Pierrepont (d. 1714), had been the minister of the First Congregationalist Church, New Haven, from 1685 till his death, and had played a leading role in founding Yale College.

Her mother, Mary Hooker, was the granddaughter of Thomas Hooker (1586-1647), one of the most influential first-generation Puritans in New England. Jonathan Edwards noted in 1742 that his wife had been ‘converted above twenty-seven years ago’, that is, around 1715, when Sarah was five.

In the above citation, though, there is no mention by Jonathan of what others frequently remarked upon, namely, Sarah’s striking physical beauty. Samuel Hopkins, who lived with the Edwards family while Jonathan trained him for pastoral ministry, and who met Sarah after she had already had seven children, recalled that Sarah was ‘comely and beautiful’, in fact, ‘more than ordinarily beautiful’. For Jonathan, though, it was the inner beauty of her soul that first attracted him.

Marriage and family life

Four years after their first meeting they were married; he sporting a powdered wig and a new set of white clerical bands, she wearing a pea-green dress of satin brocade. Samuel Miller, one of the nineteenth-century founders of Princeton Theological Seminary, rightly remarked: ‘Perhaps no event of Mr Edward’s life had a more close connection with his subsequent comfort and usefulness than this marriage’.

Sarah was so adept at managing the household affairs that Jonathan was able to give himself unreservedly to his ministry. Hopkins remembered Sarah as ‘a good economist’, who ‘took almost the whole care of the temporal affairs of the family, without doors and within’. This appears to have suited her husband, who once remarked near the end of his life, ‘I am fitted for no other business but study’!

Their first daughter, Sarah (1728-1805), was born the year following their marriage. She was the first of eleven children, all of whom survived infancy. In a day when infant mortality was extremely high, this is amazing. Samuel Miller wrote: ‘Almost all his children manifested the fruit of his pious fidelity by consecrating themselves in heart and life to the God of their fathers’.

Sarah’s early uncommon spirituality attracted Jonathan to her, and Hopkins records that later in life she remained ’eminent for her piety and religious conversation’. In fact, from 1735 onwards Sarah frequently had ‘extraordinary views of divine things’, experiences which she recorded in a first-person narrative that her husband encouraged her to draw up in 1742. Later, he inserted this manuscript into one of his important defences of the First Great Awakening, Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New England (1743).

Transcendent love

She was given, we read, ‘such views of the glory of the divine perfections and Christ’s excellencies, that the soul in the meantime has been as it were perfectly overwhelmed, and swallowed up with light and love and a sweet solace, rest and joy of soul, that was altogether unspeakable; and more than once continuing for five or six hours together, without any interruption, in that clear and lively view or sense of the infinite beauty and amiableness of Christ’s person, and the heavenly sweetness of his transcendent love’.

On the other hand, there were times that she had ‘an extraordinary sense of the awful majesty and greatness of God’ and ‘of the holiness of God, as of a flame infinitely pure and bright’.

She was given ‘a sense of the piercing all-seeing eye of God’ and ‘an extraordinary view of the infinite terribleness of the wrath of God’. Little wonder that she had an overwhelming sense of the glory of the work of redemption, and ‘the way of salvation by Jesus Christ’.

Undergirding these experiences was ‘a sweet rejoicing of soul at the thoughts of God being infinitely and unchangeably happy, and an exulting gladness of heart that God is self-sufficient, and infinitely above all dependence, and reigns over all, and does his will with absolute and uncontrollable power and sovereignty’.

Edwards tells us that her soul ‘often entertained, with unspeakable delight…the thoughts of heaven, as a world of love, where love shall be the saints’ eternal food, and they shall dwell in the light of love, and swim in an ocean of love, and where the very air and breath will be nothing but love’.

Bodily phenomena

Accompanying these remarkable experiences were certain bodily phenomena which some have cited in support of the ‘Toronto Blessing’, a movement Edwards would not have endorsed. It is vital, therefore, to see them in the entire context of Edwards’ thought.

Sarah’s ‘views of divine things’, we are told, often deprived her of ‘all ability to stand or speak’. Given an ‘extraordinary sense of the awful majesty and greatness of God’, she lost all bodily strength. Another time, the ‘overwhelming sense of the glory of the work of redemption, and the way of salvation by Jesus Christ’ caused her body to faint.

Edwards was at pains to point out that Sarah’s joy was never attended ‘with the least appearance of any laughter or lightness of countenance’. Rather, it led to ‘a new engagedness of heart to live to God’s honour, and watch and fight against sin’. Nor were her experiences ‘attended with any enthusiastic [i.e. fanatical] disposition to follow impulses, or any supposed prophetical revelations’.

Edwards insisted that the Spirit of God always leads those in whom he dwells to view the Scriptures as ‘the great and standing rule for the direction of his church in all religious matters, and all concerns of their souls, in all ages’. ‘Enthusiasts’ or fanatics, on the other hand, regularly ‘depreciate this written rule, and set up the light within or some other rule above it’. In other words, Sarah’s experiences were proved genuine by her refusal to look for God in any other place but his divine Word.

Moreover, the reality of these experiences was evidenced by their fruit. As he watched his wife engaged in her daily responsibilities, Edwards saw a person who was ‘eating for God, and working for God … and doing all as the service of love … with a continual, uninterrupted cheerfulness, peace and joy’.

Eternal fruit

When Edward’s lay dying in Princeton fifteen years later, none of his family were present except for his daughter Lucy. He had come there to take up the presidency of the College of New Jersey and had left Sarah with the rest of their family back in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he had been ministering since 1750.

He had been inoculated against smallpox, which was raging in Princeton and the vicinity, but complications set in. Never a strong man physically, Edwards died on 22 March 1758. Among his last words were some for Sarah.

‘Give my kindest love to my dear wife’, he told Lucy, ‘and tell her that the uncommon union which has so long subsisted between us, has been of such a nature, as I trust is spiritual, and therefore will continue for ever’.

Edwards’ statement that he and Sarah had known a spiritual union reveals what lay at the heart of their marriage. They had had an ‘uncommon union’ because (in the words he wrote of Sarah when they first met) they both desired ‘to be ravished with [God’s] love and delight forever’.