This year marks both the bi-centenary of the birth of George Müller (1805-1898) and the centenary of the death of Thomas Barnardo (1845-1905). Both were great and godly men who lived their lives fully for the Lord, consumed by love for Christ and their fellow human beings.

With burning concern, they both devoted their lives to the welfare of children — but they were different kinds of men and went about it in very different ways. Müller was of a pietistic inclination, relying greatly on prayer as a means of meeting all his needs.

Barnardo, while also realising the need for prayer, was a practical man, full of energy and action. He literally wore himself out in the service of the Lord and died at 60, whereas Müller lived to 93. Although their lives overlapped by 53 years, Müller was 40 years older than Barnardo, so they belonged to different generations.

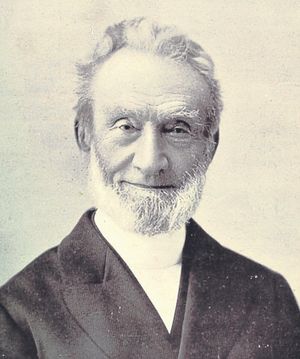

George Müller

Müller was converted in Halle in Germany in 1825. He came to England in 1829 intending to work with the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews. However, he did not agree with their policy of only preaching to Jews, so he could not be admitted as a missionary student.

Shortly after this he became the pastor of Ebenezer Chapel in Teignmouth where he met Henry Craik, who became his lifelong friend and co-worker. At this time, he became concerned that the church should not give him a stipend, but rather he should live ‘by faith’ — not even making his needs known but trusting the Lord to prompt his people to give. The modern manifestation of this principle probably originated with Müller, and he held to it tenaciously all his life.

Another milestone in Müller’s life occurred in July 1829 when — to quote from his journal — ‘I gave myself fully to the Lord. Honour, pleasure, money, my physical powers, my mental powers, all was laid down at the feet of Jesus, and I became a great lover of the Word of God. I found my all in God’.

George Müller married Mary Groves on 7 October 1830. After two and a half successful years in Teignmouth, Müller and Craik moved to Bristol, where they began to minister at Bethesda Chapel and Gideon Chapel respectively.

These churches saw the origin of the Open Brethren as we know them today — as a result of a split with the followers of J. N. Darby who became the ‘Exclusive Brethren’. In 1834 he started the Scripture Knowledge Institution. Its objects were to aid Christian day schools, to assist missionaries and to circulate the Scriptures. This Christian charity is still functioning today, helping missionaries in many countries.

Cholera

In 1834 there was a cholera epidemic in Bristol, and many hundreds died. Hundreds of orphans were left with no one to care for them, and many were reduced to begging on the streets. Seeking to help, George Müller started his life’s work for God.

George, Mary and Henry prayed about this great need for some weeks and shared their concern with other Christians. Müller also saw this as an opportunity to prove to the people of Bristol the reality of faith in God, who answers the prayers of those who trust him.

In December 1835 he wrote in his journal, ‘If I, a poor man, simply by prayer and faith, obtained without asking any individual the means for establishing and carrying on an Orphanage House, then this would provide visible proof that God is faithful still and hears prayer still’.

Over the next few months he received many gifts for the Orphan House, both in money and furniture — the first gift was a large wardrobe! By April 1836 he had received a total of £1,000 and he was able to rent a large terraced house in Wilson Street, in the centre of Bristol.

This became his first Orphan House, for girls aged 7 and over, and within a few weeks it was filled to capacity with 30 girls and two Christian ladies to look after them.

Shared vision

From then on, until 1870, the story is one of continuous expansion. After renting four homes in Wilson Street, there were some polite complaints from neighbours about the pressures caused by so many children in a residential street.

As he prayed about this, he began to dream of the benefits of having purpose-built homes in wide-open spaces on the outskirts of the city. He shared his vision with other Christians and large gifts began to come in for a new Orphan House.

He was able to purchase 7 acres of land on Ashley Down and the new Orphan House was completed in June 1849. By 1870, when Müller was 65, there were 5 Orphan Houses caring for 2,000 orphans, with about 200 staff to look after them. The money required to run them was over £30,000 per year — all raised in answer to prayer without direct appeals.

Thomas Barnado

Let us now consider Barnardo. He was born in Dublin in 1845 and almost died at birth and again came close to death when he contracted diphtheria at the age of two. Indeed, he was pronounced dead by two doctors, but revived when lifted up by the undertakers!

Thomas Barnardo was converted at the age of 17 through the Irish Revival and the witness of his brothers, George and Frederick. He was soon baptised at the Baptist chapel, without the approval of his father.

He was early convinced of the need to serve the Lord, which he did in various ways even at such a tender age. He conducted classes at ragged schools, preached to troops and to the police, and carried out door-to-door visiting in the Dublin slums.

After four years he heard Hudson Taylor speak. This caused him to resign his job with his father and volunteer to be a missionary in China. He then left Dublin for London to train as a medical missionary.

In London he was quick to see the needs of ‘street children’ in East London. He started his own ‘ragged school’ in an old donkey stable. It was here that he came across the famous Jim Jarvis who took him to see where many of his friends slept, on the corner of a roof.

In 1869 he was wrestling with the question of whether he should still go to China. What decided him was an unexpected gift of £1,000 from a Member of Parliament, Samuel Smith, towards his work in East London.

Carrots

In1870 Barnardo opened his first children’s home in Stepney, housing 25 boys whom he personally collected from the streets. One little boy, called ‘Carrots’, was refused admission one night because the home was full. Later he was found dead from exhaustion and exposure.

This greatly disturbed Dr Barnardo, who then put up a sign outside the home: ‘No destitute child ever refused admission’. This became the policy of Barnardo’s Homes throughout their history.

Barnardo was concerned to use all means to spread the gospel. In1872 he was able to purchase the ‘Edinburgh Castle’ — an infamous Gin Palace — and convert it into a ‘Peoples Church and Christian Coffee Palace’. Many thousands of people were converted through this centre.

In the winter of 1872 a girl aged eleven knocked at the door of the Boys’ Home, just about midnight and asked, ‘Please d’you take in little gels?’ The girl was in a famished condition and they found her a home.

This led to Barnardo starting a Girls’ Home. Later he realised that large homes were not suitable for girls and he housed them in groups of cottages. Barnardo married Syrie Elmslie in 1873. As a married man he felt much more at liberty in establishing homes for girls.

Fervent love

Barnardo became one of the most famous men in London and his work expanded throughout Britain and overseas. Barnardo’s is still the largest children’s charity although, like the George Müller foundation, it no longer runs children’s homes.

There is not space in this short article to make a detailed comparison between Müller and Barnardo. They were different in so many ways — except in their fervent love for the Lord and for children.

They both firmly believed in prayer and in making their needs known to God, but whereas Müller believed in prayer alone, Barnardo believed in prayer and public appeals to those who had the means to give.

He was once asked why he did not follow Müller’s example and answered, ‘I have always felt a positive duty was laid upon me, to stir up the minds of Christian people generally to a greater sense of their responsibility’.

My own view is that Müller had a specially close relationship with God, and God honoured his principles. Barnardo, on the other hand, was a man of vision and action. He did not just see a need, but took immediate steps to address it.

I have been privileged to witness — and have some part in — this kind of work today, in Caring for Life, a Christian charity based in Leeds caring for homeless people. Both Müller and Barnardo are striking examples of what people can accomplish when they are fully devoted to the Lord.