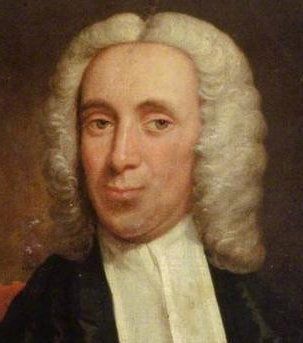

Two hundred and fifty years ago, in November 1748, Isaac Watts was called to his eternal rest. He left behind some 600 hymns, many of them paraphrases of the Psalms and other portions of Scripture, but all written in the language of the new covenant and explicitly bringing the person and work of Christ into sung congregational praise. He wrote other works too, including Divine and Moral Songs for Children, which has sold seven million copies and is still in print.

Isaac was born into a godly home in Southampton on 17 July 1674. His father was a schoolmaster and was temporarily imprisoned for his faith at the time of Isaac’s birth. Isaac was small and sickly, but well cared for in body and in soul. The influence of his home upon him was enormous, and at the age of six he composed some verses that showed not only his poetic gift but his appreciation of sound doctrine. The verses are an acrostic on his name.

‘I am a vile polluted lump of earth

So I’ve continu’d ever since my birth;

Although Jehovah grace does daily give me,

As sure this monster Satan will deceive me,

Come, therefore, Lord, from Satan’s claws relieve me.

Wash me in thy blood, O Christ,

And grace divine impart,

Then search and try the corners of my heart,

That I in all things may be fit to do

Service to thee, and sing thy praises too.’

Isaac came under conviction of sin when he was fourteen years of age and one year later, in 1689, put his trust in Christ. When he was sixteen he went for four years to a Nonconformist academy in London, and then in 1696 became tutor to the son of Sir John Hartopp at Stoke Newington.

He remained single all his life, but that was not through choice. A young lady, Miss Elizabeth Singer, was greatly attracted to Watts as a poet. She was very attractive and Watts was very attracted to her. She wanted to meet him, but when she did her heart sank. When he later proposed to her, she responded (with the best of intentions, no doubt), ‘Mr Watts, I only wish that I could say that I admire the casket as much as I admire the jewel’!

He was only five feet tall. He was once in a coffee room with some friends and overheard a gentleman remark contemptuously about his appearance: ‘What! Is that the great Dr Watts?’ With admirable presence of mind and great humour he repeated one of his own verses:

‘Were I so tall to reach the pole, Or grasp the ocean with a span,

I must be measured by my soul, The mind’s the standard of the man.’

Ministry

In 1702 Watts was ordained minister at Mark Lane Independent Chapel, the same church where John Owen had once laboured. He proved to be an excellent preacher and pastor, although the congregation complained that they saw too little of him. The congregation flourished, but Watts was frequently ill.

Watts lived during the Age of Reason and worked his brilliant mind too hard, suffering for it greatly at the end of his life. He was theologically unsettled by the major controversies of his day, with heresies such as Socinianism and deism attacking the deity of Christ. Watts tried to reconcile opposing factions amongst Christians; he speculated that Christ could have had a human soul before his incarnation. At a conference in 1719 he voted with the minority who refused to impose acceptance of the doctrine of the Trinity on Independent ministers. He had a brilliant mind and his later isolated circumstances could well have contributed to over-speculative thinking. None of this affected Watts’ hymns, however, which were written earlier in his life.

Because of recurrent ill health, Watts was forced to resign his pastorate at Mark Lane in 1712. He was invited to live in the family home of Sir Thomas Abney and there he was able for his last thirty-six years to devote himself quietly to writing. He died in 1748 at Stoke Newington, having lived to see the answer to his prayers: ‘May a plentiful effusion of the blessed Spirit also descend on the British Isles and all their American plantations to renew the face of religion there.’ He wrote,

‘Come, dearest Lord, descend and dwell

By faith and love in every breast;

Then shall we know and taste and feel

The joys which cannot be expressed.’

The answer from heaven was the great transatlantic Evangelical Awakening. This revival ensured the place of the hymn in church services. Watts’ contribution was, with others, to provide a choice hymnody, through which thousands of new converts could voice their heartfelt praise to God.

Hymn-writer

Watts’ gift for hymn-writing became apparent at an early age.

One day after attending the Independent church in Southampton, the fifteen- year-old Isaac complained to his father about the poor quality of the sung praise. It lacked the dignity and beauty that should characterize it. His father suggested that if he could do better he should get on with it! Straightway Isaac composed his first hymn:

‘Behold the glories of the Lamb,

Amidst his Father’s throne;

Prepare new honours for His name,

And songs before unknown.’

His brother Enoch encouraged him to undertake a revision of the metrical psalms. Watts believed strongly that they should be rephrased for public worship in the light of the New Testament.

Watts realized that he would be accused of ‘tampering with’ God’s Word. He prepared a Short essay towards the improvement of Psalmody (over 12,000 words!). He argued that the time-honoured metrical psalms were not close translations of God’s Word, but incorporated the additions and inventions of men. He reasoned that when we read the Bible we should indeed keep to the original, but our response to it must be our own. If we are allowed to preach and pray in our own words, then why can we not sing in our own words, for there is no essential difference between prayer and praise? Further, are we not commanded to sing ‘in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ’ (Ephesians 5:19-20)? He believed that psalms were models of worship, not to be slavishly followed. He referred to their use in the New Testament, including Luke 19:38, where the disciples quoted Psalm 118, but in their praise added, ‘peace in heaven and glory in the highest’. He thought it was improbable that all the psalms of David were originally sung in Old Testament worship.

Above all, Watts wanted to express David’s words in the language of a Christian: ‘Where the Psalmist uses invectives against his personal enemies, I have endeavoured to turn the edge of them against our spiritual adversaries. Where the original runs in the form of prophecy concerning Christ and His salvation … there is no necessity that we should always sing in the obscure and doubtful style of prediction, when the things foretold are brought into open light by a full accomplishment … Where the Psalmist talks of sacrificing goats or bullocks I rather choose to mention the sacrifice of Christ the Lamb of God. When he attends the ark with shouting into Zion, I sing the ascension of my Saviour into Heaven or His presence in His church on earth.’

Some of the resulting paraphrases are among the best known of all hymns; for example, ‘Our God our help’, based on Psalm 90; ‘Jesus shall reign’, on Psalm 72; ‘ How pleased and blest was I’, on Psalm 122; and ‘From all that dwell below the sky’, on Psalm 117. ‘Come let us join our cheerful songs’ is a New Testament paraphrase, based on Revelation 5:11-13.

One reason why his hymns have lasted so well is that Watts took care to write with simplicity, remembering the intellectual capacity of eighteenth-century congregations and avoiding high-flown poetry. He was anxious that even the most ignorant worshipper should not ‘sing without understanding’. That is why Watts’ hymns are easier to understand than many from the nineteenth century.

Watts’ approach meant that his hymns are almost expositions of Scripture. He has left a body of divinity, with hymns closer to the meaning of Scripture than those penned by any other hymn-writer. They cover the whole range of biblical doctrine. It was his desire that worshippers should instruct each other in this way through the singing of Bible-based hymns. Spurgeon claimed that Watts’ hymns were so comprehensive that, no matter what the topic of his preaching, he could quote some appropriate verse from them.

Isaac Watts deserves to be looked at again — not only by those who claim that hymn-singing is unscriptural, but also by those who replace our precious heritage of hymnody with empty compositions. His hymns lead us to the throne of grace and exalt our majestic God and Saviour. Two hundred and fifty years after his death, millions of people still sing them the world over. The greatest hymn ever written is still, surely, this by Isaac Watts:

‘When I survey the wondrous cross,

On which the Prince of glory died,

My richest gain I count but loss

And pour contempt on all my pride.’