As a newly arrived English teacher in Japan, I used to ask my students what religion they belonged to. I was surprised when the responses came, ‘I am not religious’.

At first I thought these young people were so absorbed in materialism that they no longer saw religion as relevant. But in time I realised that, although my students professed to have no religious faith, their actions revealed the opposite. They were very concerned with religious matters!

On the surface, people in Japan are not religious. There is no tradition of meeting weekly for worship, as in Christian churches. However, people do visit Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines at certain times of the year (e.g. New Year), for important life events (e.g. weddings, funerals) or at times of crisis (e.g. illness, facing university entrance exams).

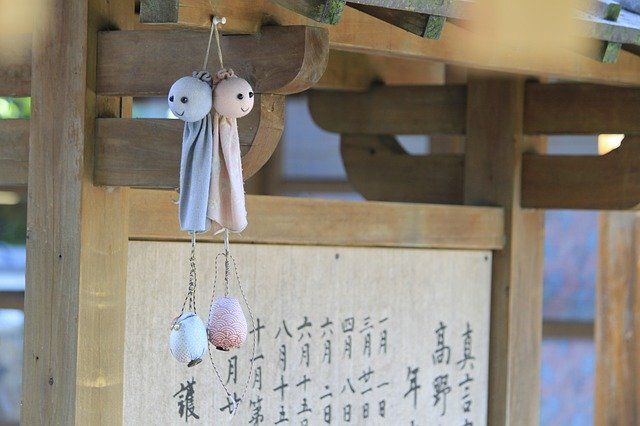

Even my ‘non-religious’ students would visit a shrine every New Year. They owned mamori or specially blessed charms to give them safety or success in their exams.

What makes the religious thought-life of the Japanese difficult for Westerners to understand is the fact that Japanese are traditionally both Buddhist and Shinto. Add to this Taoist and Confucian influences, and some local folk religion, and one has a confusing mixture of religious idea and practices.

The traditional Japanese home has both a Shinto ‘god-shelf’ and a Buddhist altar. With this mix, it is not surprising that many Japanese cannot say what they do actually believe!

Consumerism

Many Japanese have a consumerist approach to religion. People seek out the religious practice that best fits their problems or situation. It has been said that Japan is a country of 8 million gods. Although this number is figurative, it does illustrate that, when it comes to seeking spiritual answers, the Japanese see a whole variety of options.

So people absorb pieces of religious practices and philosophy from different sources. This eclectic approach means that a person’s beliefs are often inconsistent or contradictory.

Christian missionary work has been a difficult task in Japan. Though mission has been active for the last 130 years, less than 1% of the population has become truly Christian. How is this possible, when the Bible is the best-selling book in the history of Japan?

One reason is religious consumerism. Many Japanese would be happy to absorb a little of Jesus Christ’s teachings into their lives, along with their Buddhist and Shinto beliefs. But the exclusivity of the gospel message is a stumbling block. The idea that one has to give up all other faiths and practices, including veneration of one’s ancestors, is seen as a rejection of family and national heritage.

Culture

A second challenge is that many religious practices and ideas have come to be equated with the culture. Certain festivals and ceremonies are viewed as ‘cultural’ events, although they are in fact religious in nature.

For example, every November, girls who are seven or three years old and boys who are five years old, are dressed in traditional kimonos and taken to the temple or shrine for a special blessing.

Although the ceremony takes place at a temple or shrine, many do not consider it a religious ceremony. Not to take a child to the festival at the appointed age is seen as depriving it of part of its cultural heritage.

Ancestor worship

One of the most difficult religious ties to break is the responsibility Japanese feel towards their deceased relatives. Funerals, memorial services and yearly visits to the family grave are deeply rooted in ancestor worship.

To decline to take part in these Buddhist ceremonies is seen as abandoning one’s family obligations. For new Christians, the pressure to take part in rituals at the family grave is very great.

Many people are searching for meaning outside of traditional Japanese religions. There has been an explosion in the number of ‘new religions’ in Japan. Some are benign offshoots of Buddhism, while others are dangerous cultic groups following dynamic leaders. A good example of the latter is Aum Shinrikyo, the cult that made a poison gas attack on the Tokyo subway five years ago.

Growing discontent among young people towards their families, and Japanese society in general, may yet serve to bring a new openness to the gospel. The growth of new religions shows that spiritual hunger is increasing. Although Japanese culture has long resisted Christianity, it is the prayer of many that God will soon bring about revival in Japan.