The green and pleasant little Belgian village of Passchendaele, just east of Ypres, has given its name to some of the worst horrors of the First World War. It has become synonymous with the mud of Flanders.

With the Somme, you think of over-the-top charges and thousands of British soldiers mown down by German machine guns. With Passchendaele, you think of mud. Just over 100 years have elapsed since that particular campaign ended in ignominious abandonment, but the images have entered our collective psyche and are still with us today.

Everyone knows that it rained then and that it rained hard. In fact, the rainfall in low-lying Belgium in August 1917 was the worst they had experienced for 30 years. However, that was not the whole story.

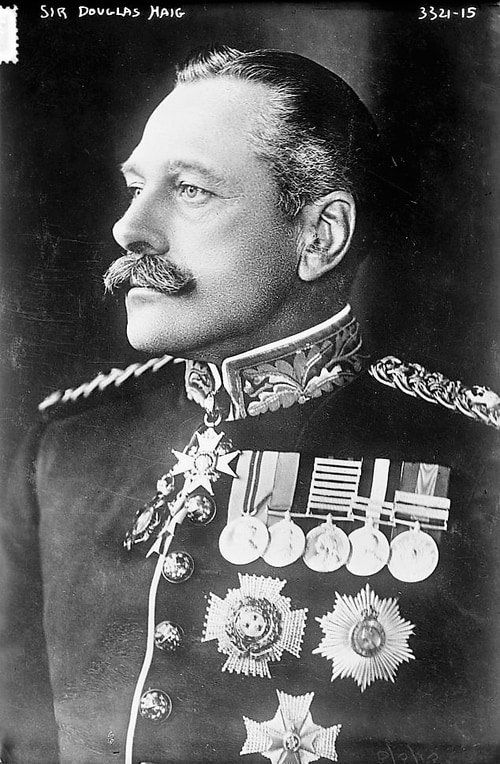

General Douglas Haig had been warned that his plan to subject German positions to a massive bombardment before advancing out of Ypres would have dire consequences for the terrain. Marshland reclaimed over centuries and kept intact with an elaborate system of drainage ditches would revert to marshland again if the drainage system was destroyed.

Haig ignored the advice. As predicted, land made solid over centuries of careful management was reduced to a quagmire in a single hour. An unrelenting barrage of shell-fire exploded into sodden turf, turning green fields brown. Leafy woods were reduced to a flat, apocalyptic landscape of barrenness, marked by protruding stumps of broken tree trunks.

If Allied soldiers were to die in the mud, it was the Allied command that had been the significant factor in creating the mud in the first place.

Lives lost in mud

Militarily it was a disaster. The aim was to lead an assault that would absorb German troops and eventually break out to the coast, where Haig wanted to nullify the U-boat threat from occupied Belgian ports. But the Allies had effectively destroyed their own intended route leading eastwards from Ypres. They had also wiped out any prospect of cover for advancing men.

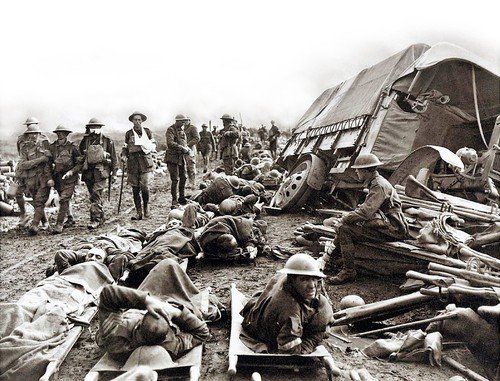

Progress was incredibly slow. Troops inched forward, wading in mud. It could take over an hour to rescue anyone who sank down to their arm-pits. Tanks became immobile and broken down in the churned-up mud. Rifles and machine guns jammed. Horses, tanks and men all became sitting targets for Germans.

The stinking mud itself claimed many victims. Duck-boards were laid, but anyone slipping off was in instant danger. Many who did so were sucked to their death in the thick ooze. A soldier might lose his footing in the dark and not be seen again.

One British soldier recorded how he had tried in vain to rescue a man from the mud. He wrote, ‘I shot this man at his most urgent request, thus releasing him from a far more agonising end’.

Normally a shell crater could be relied upon to provide temporary cover for any wounded soldier until rescue arrived. Some seriously injured and immobile soldiers, placed in a shell hole for protection, faced death by drowning. They could only watch helplessly as the water level slowly rose.

Lives lost for mud

The campaign, which like so many others had begun in optimism, ended in disillusionment and ultimate failure. It was not a defeat as such, but it was a very long way from a victory.

What had started at the end of July 1917 ended in early November, when Haig finally accepted that he was getting nowhere. An ordeal for the troops that had lasted nearly four months had taken them less than five miles. And what was it all for? Military historian John Keegan says that all that was left of Passchendaele when they finally got there was a ‘smear of brick’.

Men were not only fighting in mud, they were also fighting for mud. A corporal in the army wrote, ‘Fancy fighting Germans for a land like this!’ An estimated 70,000 Allied troops had paid for a stretch of quagmire with their lives. A highly placed officer from HQ paid his first visit to the front and broke down in tears, ‘Did we really send men to fight in that!’

Indeed, they had! Haig had urged politicians to accept his advice that this was a critically important military manoeuvre and had to be carried out. Bolstered by a false confidence, he persisted with his plans long after it was obvious that success was impossible.

Alan Brooke, the future Chief of the Imperial General Staff who loyally supported Churchill in the Second World War (although also prepared to stand up to him), was present at Passchendaele. He was staggered by Haig’s rosy optimism, which seemed to bear no relationship to reality.

He was convinced that Haig had never seen the mud for himself. Safely housed in command HQ, Haig had presumably directed his orders after moving flags around on a board.

Gospel parallels

People are right to talk about the military lessons of the Somme or Passchendaele, but there are also some spiritual parallels. Mankind is wallowing in a sea of mud. It may not feel like that, but we have learned to accommodate ourselves to an environment which will ultimately suck the very life out of us.

Genesis 1-3 teaches us that this is a deadly environment of our own making; we made the mud. In sinful rebellion, man ruined creation through his sin, so that the world in which we live has become a quagmire of moral decay. Our actions were knowing and culpable; we have no excuse.

This is not merely the environment in which we live, but the environment that we live for. More than that, we die bewailing the fact we are leaving it. And yet it is only a stretch of worthless swamp. Fancy fighting for a land like that!

In contrast to some of the senior officers in Ypres, God was neither remote nor aloof. He looked and saw our helpless misery. Self-inflicted it may have been, but he took pity on us.

And so, as we remember at Christmas, Jesus Christ came down and joined us in our hopeless mess. He too wallowed in our man-made slime, although, unlike us, he added not one speck of moral decay to it.

He shared our plight and finally surrendered himself to the overwhelming ‘mud’ of being punished for our sins at Calvary. Triumphantly he conquered the grave and rose again. His death means life for those who seek his forgiveness now.

‘I waited patiently for the Lord; he turned to me and heard my cry. He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire; he set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand. He put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and fear and put their trust in the Lord’ (Psalm 40:1-3).

Paul Mackrell lives in West Sussex