In the New Testament, the word ‘cross’ invariably refers to the instrument on which Jesus Christ suffered death. The Greek word properly signifies a stake, or upright pole; but the Romans modified this form of punishment and scholars have therefore found it difficult to determine the precise form of our Lord’s cross. It is possible that he was nailed to a simple stake (the cna simplex), but it is more likely that he died on a stake with a transverse beam near its top (the crux immissa). There is nothing in the Gospels to enable us to determine this matter with certainty, although Christ’s ‘accusation’ fixed ‘over his head’ may suggest a projection above the horizontal beam (Matthew 27:37).

What we do know is that the more elaborate cross, consisting of two pieces of wood, was in general use in the first century and, certainly, the ancient voice of tradition is in favour of it. Justin Martyr (A.D. 110165), one of the earliest of our Christian writers, testifies to the fact that this was the form employed. In a description of Christ’s crucifixion he says, ‘The one beam is placed upright … the other beam is fitted on to it.’

The idolatrous Church of Rome has made a sacred symbol of the cross. In Romish churches, crosses are set up and the faithful are encouraged to kiss them and to bow the head and bend the knee before them. Historically, Protestants have shunned all use of material crosses; but nowadays it not uncommon to find them on Protestant church buildings and even within those buildings, set up before the congregation. It has become increasingly fashionable to wear a cross on a badge, brooch, or necklace. This is to be deplored for the following reasons:

1. Crosses are images and the Law of God strictly forbids the use of images: ‘Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image…’ (Exodus 20:4). Accordingly, the images of the Canaanites were destroyed by fire and even the silver and gold from them was not kept because it would prove a snare to God’s people and lead to their destruction (Deuteronomy 7:25-26). ‘Little children, keep yourselves from idols’ (1 John 5:21).

2. The cross as a symbol has its origin in paganism, not Christianity. Long before the coming of Christ, it was a common heathen symbol almost universally adored. It is to be found among Egyptian and Assyrian remains; and, perhaps even more significantly, it is known to have been venerated by the Babylonians as the initial T of Tarnmuz, one of their gods. In pagan Rome, it appeared on standards and coins, and the Vestal Virgins of Rome wore it suspended from their necklaces. ‘Thus saith the Lord, Learn not the way of the heathen’ (Jeremiah 10:2).

3. Even if claimed as a specially Christian sign, there are inherent dangers with a material cross. Remember the brazen serpent. It too had sacred associations; but because the people regarded it superstitiously, Hezekiah ‘brake [it] in pieces’ (2 Kings 18:4).

4. When the apostle refers to ‘the cross’, he clearly means the doctrine of the gospel (l Corinthians 1:18; Galatians 6:14). A visible cross is a poor substitute for the glorious gospel of the blessed God. As Calvin correctly states, ‘Paul testifies that by the true preaching of the gospel “Christ is depicted before our eyes as crucified” (Galatians 3:1). What purpose does it serve for so many crosses – of wood, stone, silver, and gold – to be erected here and there in churches?’ Should some urge the need of a visible sign, we already have baptism and the Lord’s Supper, both of which represent to us Christ and the benefits of the New Covenant (1 Peter 3:21, 1 Corinthians 11:26). The Word and the symbolic ordinances: these are all we need.

5. It is significant that nowhere in the New Testament is the sign of the cross referred to. Therefore, any use of it in worship must spring from human ingenuity, not divine authority. This is precisely what Paul reprobates as ‘will worship’ (Colossians 2:23).

6. The early Christians avoided the use of this symbol. Dean Burgon writes: ‘I question whether a cross occurs in any Christian monument of the first four centuries.’ Eventually, of course, reproductions of the cross did appear and it was an easy transition from the sign of the cross to the form of the crucifix.

7. We observe that the Reformers were united in their determination to rid the church of both crosses and crucifixes, and so successful were they that, in 1574, Archbishop Whitgift was able to say: ‘As for the papists, we are far enough off from them; for they pictured the sign of the cross and did worship it; so do not we; they used it to drive away spirits and devils; so do not we; they attributed power and virtue unto it; so do not we; they had it in their churches, so have not we.’

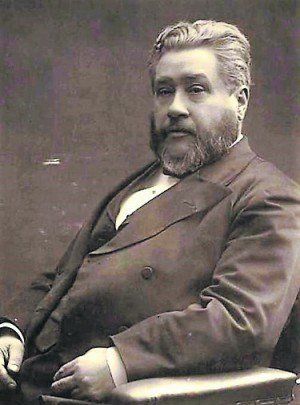

In the last century Charles Spurgeon wrote: ‘There are some who can adore a cross of wood or stone or gold; but I cannot conceive of a greater wounding of the heart of Christ than to pay reverence to anything in the shape of a cross. Methinks the Saviour must say, What! What! I am the Son of God, and do they make even Me into an idol! … We have nothing to do with these outward symbols now.’

As Protestants and Evangelicals, we should allow no material cross in our church buildings and we should oppose the trend to restore it as some kind of ornament. A relic of idolatry, it can only be an offence to almighty God