Have you ever spent a sunny summer afternoon wandering around Helmsley in Yorkshire? If so, you may have enjoyed sipping tea in one of the many cafes, browsing through second-hand bookshops or even savouring the exotic ice-creams available locally. But it would certainly add significance to any future visit to Helmsley to know something of the grace of God to that town in the past.

Stranger to forgiveness

Dr Richard Conyers began his ministry in Helmsley parish church in 1758, at the same time that Whitefield and the Wesley brothers were travelling the country on horseback, and William Grimshaw was preaching in Haworth and itinerating throughout Yorkshire and beyond.

But when Conyers first started to preach he was himself a stranger to the grace and forgiveness of God. Unlike many of the clergy of the time, however, he was zealous and conscientious, conducting his ministry with diligence and seriousness.

He did all in his power to raise standards in his parish, visiting his people and speaking privately to individuals. He even established a ‘concert of prayer’ for his young men, stipulating that as the clock struck a certain hour, each should find some private place and there pray, joining in spirit with the other young men of the parish.

Respected and regarded as eminently holy, Dr Conyers nevertheless grew uneasy when he read in the Scriptures, ‘Woe unto you when all men speak well of you’. Certainly, he thought, these words must include him in their condemnation for everyone held him to be a saint.

But how to silence the voice of conscience, Richard Conyers did not know. Perhaps he should redouble his search for holiness. So he fasted more frequently, making solemn covenants to live unreservedly for God and sometimes signing these resolutions with his own blood.

Unsearchable riches

Nothing availed to bring Conyers relief of conscience. One day as he was reading the Scriptures in a public service of worship, he was arrested by some words in Ephesians 3 where the apostle Paul speaks of ‘the unsearchable riches of Christ’.

This was an entirely new concept to the troubled vicar. ‘The unsearchable riches of Christ’, he mused. ‘I never found, I never knew, there were unsearchable riches in him’. Clearly there were depths in the Christian gospel which he had not yet plumbed.

Then another thought began to distress him. If this were true, then not only was he himself in spiritual ignorance, but he had also led his people astray.

End of the quest

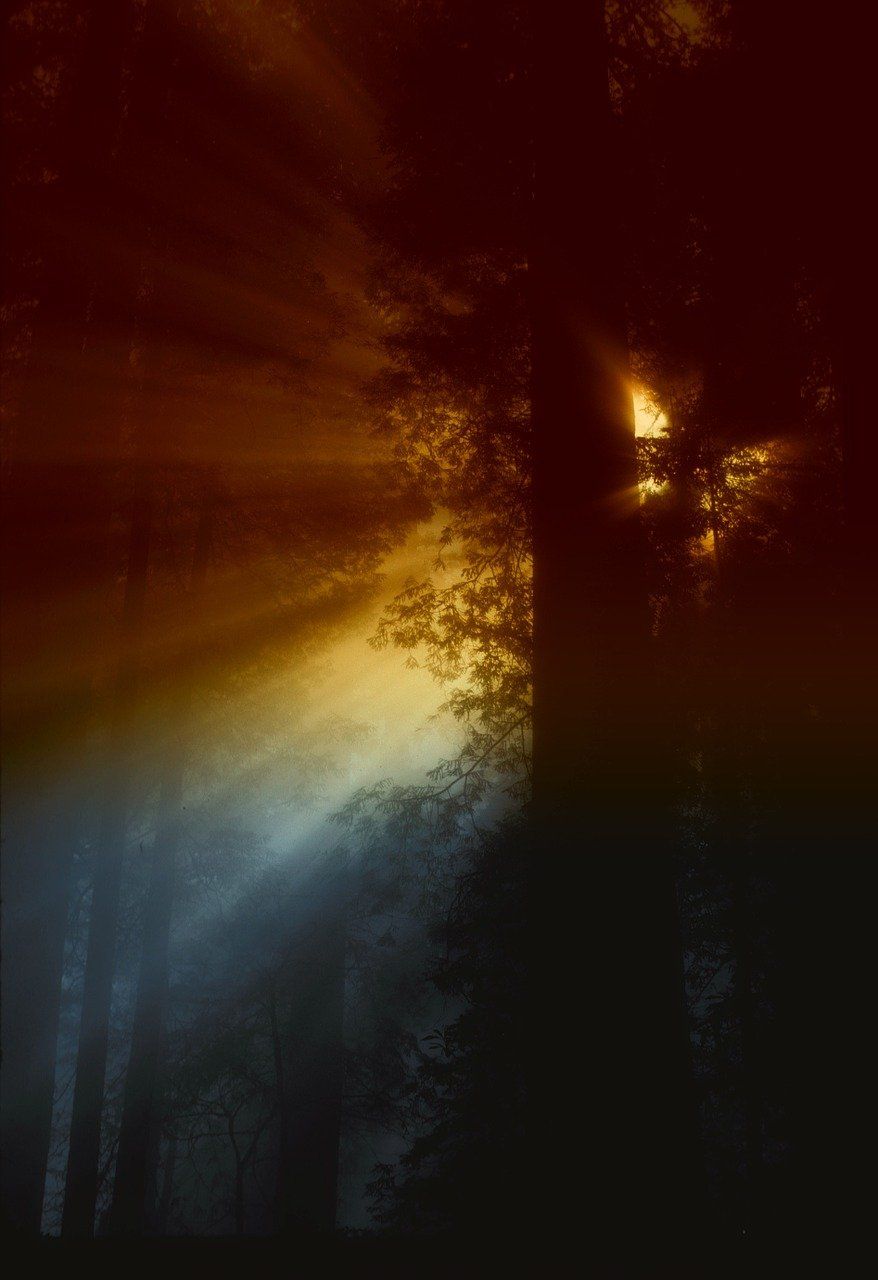

On Christmas Day 1758, Conyers’ anxious quest ended at last as God dispelled the mists of his ignorance and poured the light of his truth into his soul. When he was walking slowly up to his room, two passages of Scripture flashed into his mind. One was Hebrews 9:22: ‘Without the shedding of blood there is no remission’, and the other was 1 John 1:7: ‘The blood of Jesus Christ, his Son, cleanses us from all sin’.

Light and joy flooded over him, and he describes the effect: ‘I went upstairs and down again, backwards and forwards in my room, clapping my hands for joy, and crying out, “I have found him – I have found him – I have found him whom my soul loveth!”, and for a little time, as the Apostle said, whether in the body or out of it I could hardly tell’.

Work of grace

Such is the account of the conversion of Richard Conyers. Speedily he invited his friends to his house to tell them of God’s dealings with him. Word quickly spread of the strange things the new vicar was now saying and the next Sunday a numerous congregation gathered to hear him.

He frankly acknowledged to his astonished people that he had himself been in spiritual darkness until that very week and had misguided them in his preaching. Now he urged upon his congregation the same salvation that had brought him such relief and joy. So began a remarkable work of grace in Helmsley as large numbers of the people were converted.

Richard Conyers soon discovered that now all did not ‘speak well of him’. Anger and jealousy flared up amongst the other clergy against the earnest vicar of Helmsley, and they plotted how they might silence him.

At last the Archbishop of York, hearing the many complaints, asked to hear Conyers preach. ‘If he dares to preach his Methodism in the presence of his Grace’, thought his antagonists, ‘his gown will soon be stripped over his ears’. After his sermon the archbishop, clearly highly displeased, snapped, ‘Well, Conyers, you have given us a fine sermon!’

‘I am glad that I have your Grace’s approbation’, replied Conyers. ‘Approbation! Approbation!’ snorted the archbishop. ‘If you go on preaching such stuff you will drive all your parish mad’.

Greatly loved

But Conyers was not intimidated, nor did the archbishop defrock him as the other clergy had hoped. Instead he continued preaching with marked success, seeing an increasing number of conversions. Whenever Whitefield or other preachers of the eighteenth-century revival were in the area, he would gladly welcome them to his pulpit, though he himself could rarely be coaxed to itinerate beyond parish bounds.

So greatly was he loved by his people that, when he accepted a call to Deptford in 1767, the whole town appeared to be in mourning. Many declared that they would lie across the road to prevent his carriage from leaving. In the event, Conyers had to slip away in the middle of the night to avoid the anguish of parting.

The quality of Richard Conyers’ warm spiritual ministry can best be illustrated by the words of a prayer found in one of his letters to the Countess of Huntingdon: ‘O thou adorable Lord Jesus, what should we talk of, or think of, or write of, or glory in but thy blessed self, who art altogether lovely! … If we are so happy in his love when we cannot see him, Oh! what will we be when we are made like him and shall see him as he is?’