Commemorations of the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 have grabbed many headlines this year, as we celebrated in 2015 the 200th anniversary of that historic victory by the Duke of Wellington’s forces.

Hailed among the finest of all British military commanders, Wellington has often been compared with the Duke of Marlborough, whose momentous victories 100 years earlier also changed the face of Europe.

Casualties in war are always fearful. After the Battle of Ramillies, fought near Maastricht in 1706, 3000 of Marlborough’s men lay dead or wounded. Among them was 18-year-old James Gardiner.

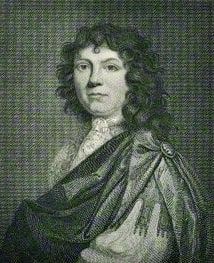

Courageous and unafraid, James was a Scottish boy born into a family with strong military traditions. Despite a religious upbringing, James had no time or thought for God, his only ambition to achieve glory on the battlefield. But now he lay bleeding from the bullet wound that had struck him in the mouth.

Night fell. James became ever weaker. Early next morning, looters streamed out of a nearby village, killing survivors and plundering the dead. ‘Do not kill that poor child’, James heard someone say, as a threatening sword was held high above him. Rescued from imminent death by a kindly friar, James soon recovered, but still had no thought of God.

The first to be told of this remarkable change was his mother. The next to hear were his officers and the men who served under him. ‘The major has gone stark mad’, reported some. In fact Gardiner had never been saner.

Promotion

With the courage of a lion, the young man rose swiftly in the army and soon found himself promoted and then awarded a commission in the regiment of the Scotch Greys. Further honours followed in quick succession, until Gardiner received the command of a regiment of the King’s dragoons.

Only two things mattered to the young officer: his prowess on the battlefield, and certain clandestine conquests of any attractive woman whom he met in his leisure hours. Night after night, he could be found flirting with any foolish enough to be lured by his handsome appearance and winsome personality.

But, despite all his achievements and all his admirers, Gardiner was not happy. Carefree and casual outwardly, he struggled inwardly to reconcile his dissolute personal life with standards and truths he knew to be right.

On one occasion, a fellow officer congratulated him on a sexual conquest he had recently made. Just at that moment a dog entered the room. ‘I wish I were that dog’, thought the troubled man. At least the dog will not have to face any final judgement.

Then came a Sunday evening in July 1719 — a date the 31-year-old would never forget. With his day’s duties complete, Gardiner had an hour to kill before his next ‘appointment’ — a midnight rendezvous with a married woman.

Returning to his quarters, he paced restlessly around. Bored, he picked up a book, blew off the dust and began to read with a candle as his only light. Suddenly a blaze of light flooded across his page. He glanced up in surprise. Had the flare come from the guttering candle?

No, it was burning as steadily as before. He raised his eyes higher and what he saw astonished and frightened the proud major, riveting him to the spot. Shining above him he saw a representation of the Lord Jesus Christ dying on the cross.

Radiating outwards, a bright light filled the room, penetrating the darkest corners. Dumbstruck, Gardiner gazed at the vision, transfixed, amazed. Then he heard a voice — or was it a voice? Afterwards he was not quite sure. ‘O sinner,’ said the voice, ‘did I suffer this for you, and are these your returns?’ He had no answer. Gradually, as he gazed, the vision faded.

How long he sat there, scarcely able to move, he never knew. All thoughts of his midnight liaison were forgotten. At last he rose from his seat in a storm of passion and grief and paced back and forth until he was almost fainting with exhaustion.

Conversion

Had he, the popular, successful military man, spent all his life crucifying the Son of God again by his sins? Scenes from his past flashed in accusing succession before his eyes: his mother’s prayers; the intervention of the friar; his many escapes from danger; and then his own ugly way of life, the sordid sins that had polluted both mind and body. Only one punishment was surely his due — hell.

James Gardiner expected no mercy. For three months he remained in a state of remorse. But, as time passed, a small flicker of hope began to kindle in his mind. Perhaps God would yet show him grace. At last, in October 1719, he heard a sermon based on a verse in the Epistle to the Romans that declared to the broken man that God was prepared to grant a full ‘remission for sins that are apast’, and the gift of Christ’s goodness in place of his own ugly record (Romans 3:24-25).

The flicker burst into a flame of joy. Gardiner was ecstatic with relief and gratitude to God. For three nights he could scarcely sleep for, as he afterwards expressed it, ‘Glory seemed to overwhelm my soul’.

The first to be told of this remarkable change was his mother. The next to hear were his officers and the men who served under him. ‘The major has gone stark mad’, reported some. In fact Gardiner had never been saner.

As the years passed, Gardiner gained a reputation for kindness and fairness in his dealings with those under his command. Many could only wonder at the changes they saw in him. And, in response, his soldiers loved him and performed their duties with an eye to pleasing him.

Not until 1726, when he was 38, did James Gardiner marry. Unselfish and gentle, Lady Frances Erskine proved an ideal wife for an army man, not complaining when James’s military duties took him to the Continent, where his regiment was frequently billeted.

Bonnie Prince Charlie

At home things seemed largely peaceful under the benign Prime Minister, Robert Walpole. But, in fact, secret plots were being hatched in the French court, plots to put Charles Stuart — known as Bonnie Prince Charlie — on the English throne.

Many were prepared to fight for the restoration of the Stuarts if circumstances were right. And in 1745 they were.

On 23 July Charles landed in the Outer Hebrides. A few days later he crossed to the mainland. Rumours began seeping through of a forthcoming Jacobite uprising, but George II and the army generals largely discounted them as mere hearsay. Before long, however, alarm bells rang, when it was rumoured that Perth had fallen to a surprise attack and Jacobite rebels were advancing steadily towards Edinburgh.

Sir John Cope, Commander-in-Chief of the Scottish army, eventually sent a small and largely untrained troop south from his Inverness base. Meanwhile, the Highlanders were sweeping onwards, armed with anything they could lay hands on: pikes, pitching forks, scythes, as well as an assortment of armaments.

Colonel James Gardiner and his regiment marched hastily up the country, for by mid-September the alarming news came through that Edinburgh had fallen.

Fast action was needed if George II’s forces were to stand any chance of halting the advance of the Highland troops in their present euphoric mood. Gardiner knew this only too well. Meeting up with Sir John, at Prestonpans near Edinburgh, he urged immediate surprise attack. It was their only hope, he insisted.

But, to his utter dismay, Sir John seemed in no hurry, preferring to answer the enemy’s first moves with a counter-strategy. Recognising that this undoubtedly spelt defeat, Gardiner could only reply, ‘I have one life to sacrifice for my country’s safety and I will not spare it’. As daylight faded on 19 September 1745, Gardiner was seen walking alone lost in thought.

Prestonpans

Scarcely had first light of dawn streaked across the Scottish sky, when a ghastly cry broke the silence, followed by sickening yells and furious volleys of gunfire. The enemy had struck.

Rebel troops swarmed across the large open field that lay between the camps, brandishing their weapons, slashing their scythes to right and left, mowing down any man or horse who charged forward to meet them.

Gardiner and his men dashed into battle, but almost immediately he received a wound in the chest. His dragoons who made up his left flank wavered, broke ranks and fled. Despite the searing pain, Gardiner fought on, though now dangerously exposed. Suddenly another shot hit him on his right thigh. Desperately he tried to rally the remnant of his regiment, but soon discovered that most had fled.

His faithful bodyguard, John Foster, remained at his side, but begged his master to retreat before he received a fatal wound. At that very moment, a Highlander rode menacingly towards them brandishing a scythe tied to the end of a long pole.

He rushed at Gardiner, and with one aggressive swipe deeply wounded him in his right arm. His sword dropped and the brave colonel fell from his horse. ‘Take care of yourself,’ he shouted to Foster.

Another Highlander, recognising that the man on the ground was a valued prize, struck him a final desperate blow on the head. The last words Gardiner was heard to articulate before he lost consciousness were said to have been, ‘You are fighting for an earthly crown. I go to receive a heavenly one’.

Heavenly crown

The battle was over in five short minutes. The excited Highlanders raced on their victorious way. King George II’s troops had been routed. Foster ran for his life to a nearby mill, exchanged his battle dress for a disguise as a miller’s servant, and taking horse and cart returned to the battlefield.

The last service he could render his honoured master was to retrieve his body. All was quiet: the roar of battle had been exchanged for an eerie silence.

Finding Gardiner not yet dead, Foster laid him as carefully as he could in the cart and set off across the field to a nearby village. But, by eleven o’clock that morning, the trumpeters of heaven sounded a clarion call of victory for Colonel Gardiner as he passed beyond the pain and noise of battle for ever to receive that heavenly crown.

Faith Cook has written extensively in Christian biography, including books on Lady Jane Grey, John Bunyan, Selina Countess of Huntingdon, and William Grimshaw