‘The disciples were first called Christians in Antioch’ (Acts 11:26). This was around A.D. 43, a decade after the crucifixion, resurrection and ascension of Christ, and the Day of Pentecost. Evidently, it was only gradually that it became possible to distinguish Christianity as a religion in its own right. Until then, the followers of Jesus were seen as a new sub-division within Judaism.

By now, however, something new was happening. Increasingly, Gentiles were being welcomed into the church without having to be circumcised. For all the continuity with the people of God of Old Testament times, there was an aspect of newness that made the Christian church a distinct movement.

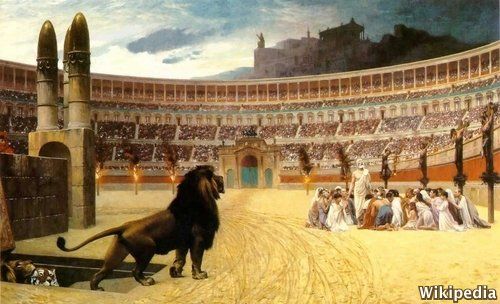

Rome burns

Acts 11:26 shows that ‘Christian’ was a well-known term by the time Acts was written (around A.D. 63 — thirty years after Christ). In fact, that was already true a few years earlier. King Agrippa said to Paul, ‘You almost persuade me to become a Christian’ (Acts 26:28). The term was clearly familiar to him.

The only other place where the word ‘Christian’ occurs in the New Testament is in Peter’s first letter, which was also written around A.D. 63. In 1 Peter 4:16 Peter reminds his readers that being a Christian could lead to suffering. Peter himself was soon to die, probably the following year at the hands of the Emperor Nero. Paul would follow shortly afterwards. It happened like this.

On 19 July 0064 a large part of Rome was destroyed by a great fire. There were many deaths, and thousands were left homeless. Before long the suspicion arose that Nero himself had been responsible.

To deflect criticism away from himself, Nero looked for someone else to blame, and settled on the Christians. This was not too difficult, because they were not terribly popular in Rome just then.

The main reason was that they had broken with the pagan practice of offering sacrifices to the gods. Obviously, to offer such worship would have been wholly incompatible with their confession that Jesus alone is Lord. But to their fellow Romans they were unpatriotic. The whole atmosphere was one of growing hostility to Christianity.

Perhaps when Peter wrote about ‘the fiery trial which is to try you’ (1 Peter 4:12) he could already sense that things were ‘hotting up’, though he probably did not foresee that the ‘fiery trial’ would literally be connected with a fire.

Scapegoat

We might well ask why a Roman emperor would burn down his own capital city. Nero was very concerned with what, today, would be called ‘image’. This may have been the immediate reason for starting the fire. He wanted to improve the appearance of the city by getting rid of an unsightly area so that he could rebuild from scratch (and extend his own palace in the process).

Nero was not particularly antichristian; he just needed a scapegoat to get himself off the hook. However, his action set a precedent, and for the next 250 years persecutions of Christians broke out in various places from time to time.

Twenty-five years later (around A.D. 90) Emperor Domitian turned against the church and exiled John, the last surviving apostle, to a small island in the Aegean Sea called Patmos.

But isn’t it wonderful how God turns things around? He uses the hostility of wicked men to advance his own great plan. While on Patmos John was given The Revelation of Jesus Christ.

He saw that Christ, not these Roman emperors, was the real power ruling the world. In the end, triumph is guaranteed to the ‘King of kings and Lord of lords’ (Revelation 19:16). What uplifting encouragement for the followers of Christ in days of darkness and difficulty!

The worst persecutions

The two worst persecutions took place, respectively, in A.D. 250, during the reign of Emperor Decius, and 53 years later when Diocletian was on the throne. The persecution by Decius was the first to be organised on an Empire-wide basis. Previous ones had been occasional, and limited to certain areas.

Decius was prompted to introduce a new policy of hostility to the church by the attitude of the Christians to Rome’s millennium celebrations, when his predecessor, Philip, was on the throne. A.D. 247 marked the 1000th anniversary of the founding of Rome by Romulus and Remus. The occasion was marked by special games and was celebrated with great pomp and ceremony. The Christians chose not to join in, because the celebrations included pagan worship.

Philip took no action. He had always maintained a policy of toleration. But Decius, who came to the throne in 249, was a different kettle of fish. He was determined to retaliate. He found the Empire in a state of decay, and held the Christians responsible. He believed that the gods were taking revenge for the widespread rejection of paganism.

Decius, therefore, made it compulsory to sacrifice to the Roman gods, and every citizen had to have a certificate confirming that he had done so. Anyone unable to produce one faced prison or even execution. This persecution lasted from about January to October 250.

Fierce interrogation

The persecution by Diocletian was even more severe. On 23 February 303 an edict was passed ordering all church buildings to be destroyed. All Bibles were to be confiscated for burning, and Christians were forbidden to meet for worship.

In the early summer of the same year, a second edict required all church leaders to be arrested and imprisoned. However, this led to problems, because the prisons were not big enough!

So a third edict in November said that the church leaders must sacrifice to the gods and would then be released. Any who refused would be executed. A programme of fierce interrogation and torture followed, in an attempt to persuade Christian leaders to give in.

Then in the spring of 304, a day of general sacrifice to the gods was proclaimed. Every citizen must take part, or else they would face either death or forced labour in the copper mines (which usually resulted in death before long). This last edict was actually passed by Diocletian’s deputy because the emperor himself was ill.

Heroism

One effect of the persecutions was to sort out true believers from nominal Christians. Some church members did sacrifice to save their skins, but among true believers there was some inspiring heroism. Let me tell you about just one, a lady called Potamiaena, who suffered during a local persecution in Alexandria, Egypt, in A.D. 202.

Potamiaena was a beautiful young woman with considerable intellectual ability. She was a slave, and her master was not a Christian. He kept pressurising her to sleep with him, but because of her Christian convictions she was determined to preserve her purity.

Consequently, she endured many hardships at work. Eventually, fed up with her constant refusals, her master took Potamiaena to court simply on the grounds that she was a Christian. He bribed the judge to break her resolution by torture, which he tried to do, but she stood firm.

The judge then gave her some time to reconsider her position. When she came to court again he asked what her decision was. Her reply was regarded as ‘impious’ (that is, insulting to the Roman gods) and she was sentenced to death by fire. She was handed over to an army officer named Basilides to carry out the sentence.

As Basilides led Potamiaena to her death the pagan crowd hurled abuse at her. However, Basilides felt some sympathy for her and drove her insulters away. In response, she promised to pray for him, which no doubt she did as she died. Her death must have been painful; little by little burning tar was poured over various parts of her body until her life departed.

Baptised

There is a sequel to this heroic story. Some time later Basilides was asked by his fellow-soldiers to swear an oath invoking the name of a pagan god. Basilides refused, on the grounds that he was a Christian.

This was news to his colleagues, and to begin with they thought he was joking. But when he carried on claiming to be a Christian they took him to court, to test whether he was real. There he continued to acknowledge his faith in Christ, so he was put in prison. Some local Christians heard about this and came to visit him.

They asked about this sudden change. He told them that for three nights after Potamiaena’s martyrdom he had dreamt that she was standing beside him placing a crown on his head and exhorting him. He realised that her prayers for him had been answered, and he sought God for mercy. He was baptised there in prison, and shortly afterwards was beheaded.